Introduction

Percutaneous coronary interventions by means of drug-eluting stents (DES) represent the gold standard treatment for most coronary artery lesions1. However, poor long-term outcomes have been reported in the currently increasing number of complex lesions, mostly driven by some of the inherent limitations of this technology2.

The presence of multiple or diffuse calcified lesions is becoming more common and, in this context, even with modern adjuvant tools, the results are not non-inferior to coronary artery bypass grafting3. One of the possible explanations for this poorer outcome is that target lesion failure (TLF) is correlated with use of longer stents and a higher risk of stent malapposition4.

In the past decade, a tremendous effort has been made to develop alternative strategies to overcome the limitations of the increased metal length implanted in the coronary arteries. One of the most studied alternatives are drug-coated balloons (DCB), which have the ability to homogeneously transfer drugs to the vessel wall without the need for prosthesis implantation5. The encouraging results in terms of safety and efficacy of DCB reported for in-stent restenosis (ISR) and small vessel disease (SVD) have led to continuous work in refining their still unclear role in native large coronary arteries.

Current stent limitations and disadvantages

Despite the constant advances in DES technology, there remains a significant risk of stent failure due to ISR or stent thrombosis (ST)2. It appears that different mechanisms are involved in early versus late ISR. Jinnouchi et al have shown by means of optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging that early ISR is associated with the neointimal hyperplasia, while late ISR is the prerogative of neoatherosclerosis6. Of note, the rate of late/very late ST has been significantly reduced with the introduction of second-generation DES, as opposed to first-generation ones7. On the other hand, a 10-year follow-up revealed no significant differences between second-generation DES and bare metal stents (BMS) in terms of target lesion revascularisation (TLR) or ST between years 5 and 10 (1.4% vs 1.3%; p=0.96; 0.6% vs 0.4%; p=0.70)8. This is easily understandable, considering that after 18 months, a DES is just a nude metallic prosthesis.

Several classical independent predictors, including diabetes mellitus, small vessel size, total stent length, and complex lesion morphology, have all been associated with stent failure9. In a similar fashion, premature dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) discontinuation or no periprocedural antithrombotics10, stent undersizing, underexpansion and malapposition, significant edge dissection, smaller stent diameters and total stent length11 or geographical miss12 have been described as independently predicting ST. Recently published data have identified new factors influencing the efficacy of DES and predictors for treatment failure, such as the history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, high remaining levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and a higher neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio or monocytes1314.

What is more, patients undergoing complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) often require potent and prolonged DAPT, which increases the bleeding risk, but since many interventions are performed in high-risk frail patients, shorter regimens become a necessity in most cases1. Despite the increasing evidence of the safety of new-generation DES with shorter DAPT regimens, the risk of ischaemic and bleeding adverse events in this population remains extremely high. In the LEADERS FREE trial, the composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), or ST was 9.4% and the rate of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) 3-5 bleeding was 7.2%15. In the Onyx ONE study 1,996 high bleeding risk patients had a 21% risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), independent of the DAPT regimen duration16. Moreover, a non-negligible proportion of patients require chronic oral anticoagulation, and triple antithrombotic therapy further increases the bleeding risk1.

Drug-coated balloon technology and procedural aspects

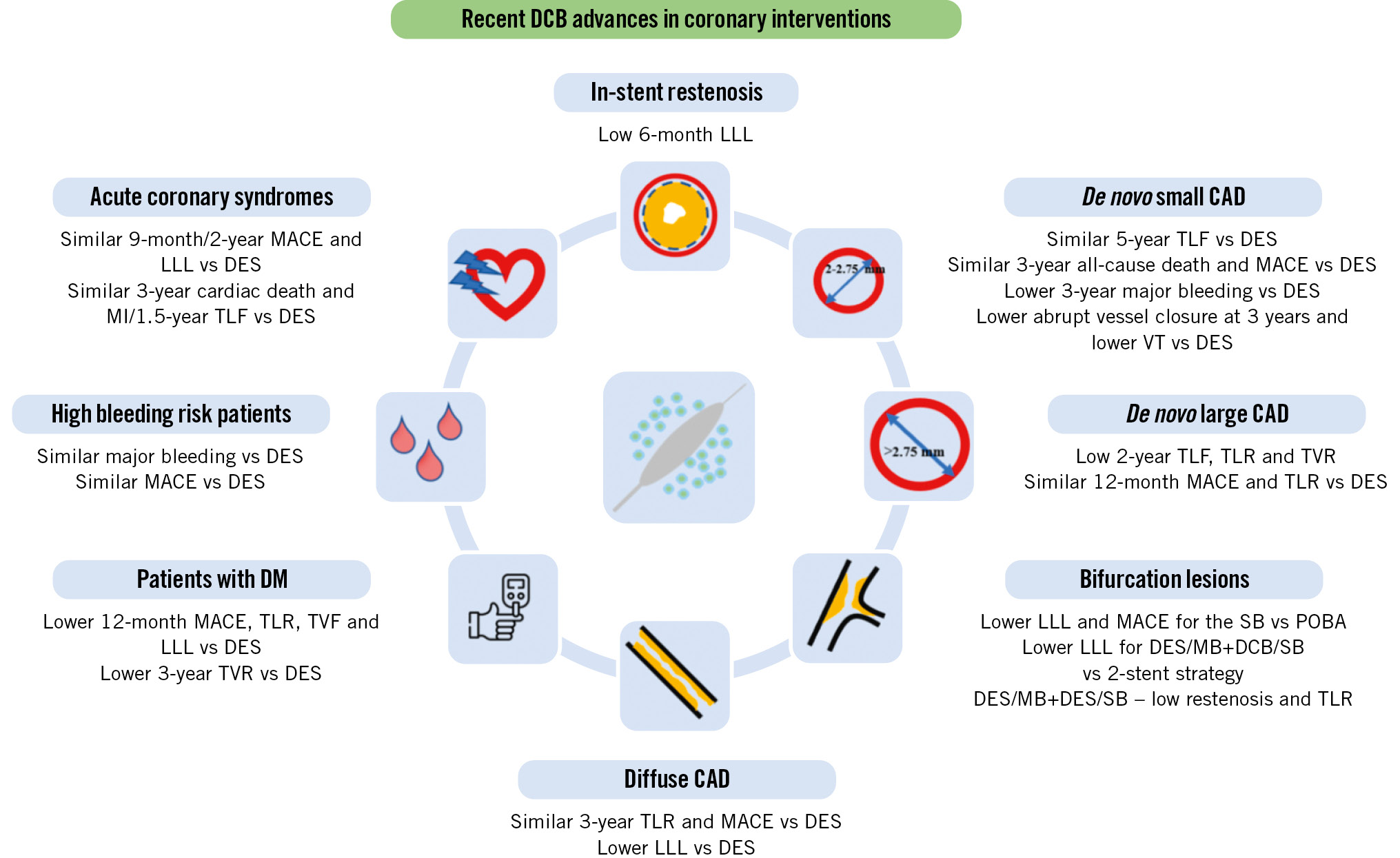

Considering all these factors, DCB have emerged as a promising alternative for tackling coronary artery disease (CAD) that seem to surpass most of the shortcomings of traditional stenting. The Central illustration depicts the potential benefits associated with their use in coronary interventions. As great heterogeneity exists in terms of balloon design and polymeric coating, paclitaxel and sirolimus are currently the only 2 antiproliferative drugs used for DCB. Paclitaxel is highly lipophilic, making its deliverability easier, and has been associated with luminal enlargement, while sirolimus offers a sustained antiproliferative effect, as shown by in vitro studies on hypoxia. A direct comparison between paclitaxel DCB (SeQuent Please NEO [B. Braun]) and sirolimus DCB (SeQuent Please SCB [B. Braun]) in the ISR setting was published in 2019, and sirolimus was shown to be non-inferior in terms of short-term late lumen loss (LLL) and midterm clinical events (12 months). Another propensity score matching analysis between the paclitaxel-coated balloon ELUTAX SV/3 (AR Baltic Medical) and the sirolimus-coated balloon MagicTouch (Concept Medical) which analysed patients from two major registries (DCB-RISE and EASTBOURNE) observed no differences in terms of TLR (7.9% vs 8.3%, respectively; p=0.879) or MACE (10.3% vs 10.7%, respectively; p=0.892) at 12 months17. However, taking into account the heterogeneity that exists in the balloon design, polymeric coating, and that the drugs used affect DCB efficacy, safety and outcome, we cannot assume that all DCBs are equal or, therefore, that a DCB class effect does not exist18.

Regarding long-term safety after DCB use, while late aneurysmal formation is a known complication of bioresorbable vascular scaffolds, there are currently no data suggesting a correlation between increased aneurysm formation and DCB. With a reported incidence of 0.6% to 3.9% after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the formation of coronary artery aneurysms after DCB use was investigated by Kleber et al in a study including 704 PCIs19. In this study, only 3 out of 380 patients developed coronary aneurysms at the 4-month angiographic follow-up, corresponding to an incidence of 0.8%, which did not exceed the general incidence after PCI.

One of the most significant features of DCB-only angioplasty for native CAD is late lumen enlargement (LLE), which was first reported by Kleber et al20. In a small study including 58 consecutive patients, the authors described at 4-month angiographic follow-up, by means of quantitative coronary angiography, a significantly increased target lesion minimal lumen diameter (1.75±0.55 mm vs 1.91±0.55 mm; p<0.001; diameter stenosis 33.8±12.3% vs 26.9±13.8%; p<0.001), with 69% of patients experiencing LLE. Similar results were reported by Yamamoto et al21, who proposed vessel enlargement, plaque regression and non-flow-limiting larger dissection after DCB treatment as possible mechanisms for this finding in a study using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging follow-up. Interestingly, in a multicentre, randomised controlled trial (RCT)22 comparing DCB with plain old balloon angioplasty, LLE was also found more frequently in small vessel disease (48% vs 15%; p<0.01), while LLL was significantly lower in the paclitaxel-coated balloon (PCB) group (0.01±0.31 mm vs 0.32±0.34 mm; p<0.01). Of particular importance, a recent study23 showed that lumen enlargement is observed in more than half of the lesions within the first year of follow-up, with 88% of these patients presenting a persistent effect at long-term follow-up (median 37 months). What is more, half of the lesions without early lumen enlargement showed late lumen enlargement after DCB angioplasty.

Similar to DES PCI, aggressive lesion preparation is mandatory when considering DCB treatment. A predilatation balloon-to-vessel ratio of 0.8-1.0/1.0 is recommended, usually starting with a plain balloon and escalating treatment (depending on lesion complexity) to cutting/scoring balloons or even atherectomy or intracoronary lithotripsy in case of severely calcified lesions24. In the absence of a flow-limiting dissection and a residual stenosis of <50%, the DCB adapted to the reference vessel diameter with a balloon-to-vessel ratio of 0.8-1.0/1.0 can be inflated to its nominal pressure for at least 30 seconds. After DCB delivery and inflation, if the angiographic result is unsatisfactory (presence of flow-limiting dissection or Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] flow <3), short bailout stenting should be considered when feasible1725.

Here, we summarise the most recent scientific advances of this technology presented or published in 2022 and early 2023.

Central illustration. Potential benefits of drug-coated balloon use for coronary interventions. CAD: coronary artery disease; DCB: drug-coated balloon; DES: drug-eluting stents; DM: diabetes mellitus; HBR: high bleeding risk; LLL: late lumen loss; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; MB: main branch; MI: myocardial infarction; POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty; SB: side branch; TLF: target lesion failure; TLR: target lesion revascularisation; TVF: target vessel failure; TVR: target vessel revascularisation; VT: vessel thrombosis

DCB USE IN IN-STENT RESTENOSIS

ISR was the first indication for DCB use for which this strategy was granted a Class I indication in the European Society of Cardiology and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (ESC/EACTS) Guidelines1.

Long-term results from important trials have recently been published, as well as head-to-head comparisons between DCB and DES (Table 1). There is a newcomer in the arena, the paclitaxel-eluting Prevail DCB (Medtronic) with the already-known FreePac technology which uses urea as an excipient. In an ISR study, authors reported low LLL rates (0.12±0.45 mm) at 6 months, as well as low rates of the need for revascularisation and of safety events at 12 months26. Some recent studies have reported DCB treatment to be moderately less effective than repeat everolimus-eluting stent (EES) implantation in reducing TLR for patients with coronary DES-ISR at long-term follow-up2728. Still, a “leave nothing behind” strategy remains of great interest, as it has been suggested to be potentially safer regarding the risk of very late stent-associated events, including lower bleeding risk, because of its shorter DAPT regimen compared with DES29. In order to further improve the clinical outcomes of patients with ISR treated with DCB, several new angiographic predictors have been described: low postprocedural quantitative flow ratio was an independent predictor of vessel-oriented composite endpoints in two separate studies3031, while the presence of in-stent calcified nodule lesions identified by OCT was associated with significantly higher rates of TLF32.

Table 1. DCB use for in-stent restenosis – results from the most recent available studies.

| Study | Design | Population | Device | Primary endpoint | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PREVAIL26 | Prospective | 50 patients (de novo and ISR) |

Prevail PCB (Medtronic) | Six-month LLL by QCA | Mean LLL 0.12±0.45 mm; 12-month TLR 7.1%, TVR 10.7% (for ISR patients) |

| Giacoppo et al27 | Meta-analysis of 10 RCTs | 2,099 patients (BMS- and DES-ISR) | SeQuent Please PCB (B. Braun); Pantera Lux PCB (Biotronik) | TLR at three years | For DES-ISR, when comparing DCB and DES, TLR was higher (20.3% vs 13.4%; HR 1.58) and MACE was only numerically lower (9.5% vs 13.3%; HR 0.69) |

| Zhu et al28 | Meta-analysis of 5 RCTs | 1,193 patients (DES-ISR) | SeQuent Please PCB (B. Braun); Pantera Lux PCB (Biotronik) | TLR | Higher TLR (RR 1.53; p=0.003) and similar MACE (RR 1.1; p=0.37) when comparing DCB to DES |

| Liu et al30 | Post hoc analysis of RCT | 169 patients (ISR) |

Shenqi PCB (Shenqi Medical); SeQuent Please PCB (B. Braun) | VOCEs (cardiac death, target-vessel MI, ischaemia-driven TVR) at one year | 20 VOCEs occurred in 20 patients; µQFR ≤0.89 predicted a six-fold higher risk of VOCE (HR 5.94; p<0.001) |

| Tang et al31 | Retrospective | 177 patients (DES-ISR) | SeQuent Please PCB (B. Braun) | One-year VOCEs | 27 VOCEs occurred in 26 patients; QFR ≤0.94 was a strong predictor of VOCE (HR 6.53; p<0.001) |

| Masuda et al32 | Prospective | 160 patients (DES-ISR) | PCB | Three-year TLF (cardiac death, TVR, definite ST) | TLF was higher in the ISR-CN group compared to the ISR-non-CN group (85.3% vs 16.9%; p<0.001) |

| µQFR: Murray law-based QFR; BMS: bare metal stent; CN: calcified nodule; DCB: drug-coated balloon; DES: drug-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio; ISR: in-stent restenosis; LLL: late lumen loss; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; MI: myocardial infarction; PCB: paclitaxel-coated balloon; QCA: quantitative coronary analysis; QFR: quantitative flow ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; ST: stent thrombosis; TLF: target lesion failure; TLR: target lesion revascularisation; TVR: target vessel revascularisation; VOCE: vessel-oriented composite endpoint | |||||

DCB USE IN DE NOVO SMALL CORONARY VESSELS

Despite robust data on the safety and efficacy of DCB in de novo SVD, an indication for their use is still lacking in the international guidelines.

Recently, long-term results of three pivotal studies comparing the outcome of DCB versus DES in native coronary vessels have been published, bringing to light the potential role of DCB in future coronary interventions.

In the final 5-year clinical follow-up of the RESTORE SVD study presented by Shao-Liang Chen during TCT 2022, similar TLF rates (8.0% vs 7.3%; p=0.85) between the Resolute Onyx DES (Medtronic) and the RESTORE DCB (CARDIONOVUM) groups were found, with optimistic results also reported regarding all-cause death, MI and any revascularisation, and no device thrombosis (Table 2).

The 3-year follow-up of the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial (vessel size: 2-3 mm) showed consistent, similar rates of MACE and all-cause death with the SeQuent Please DCB versus DES (75% EES, 25% paclitaxel DES) patients, and while major bleeding and probable or definite ST were numerically lower in the first group, they did not reach statistical significance33. Several substudies of this trial have been developed and have added some interesting results. The efficacy and safety of DCB were similar irrespective of vessel size, with a trend towards a more pronounced beneficial effect of DCB over paclitaxel-eluting stents regarding target vessel revascularisation (TVR), non-fatal MI and MACE in very small coronary arteries34; the long-term efficacy and safety of DCB were similar in patients with and without chronic kidney disease, with significantly fewer major bleeding events in the DCB group35.

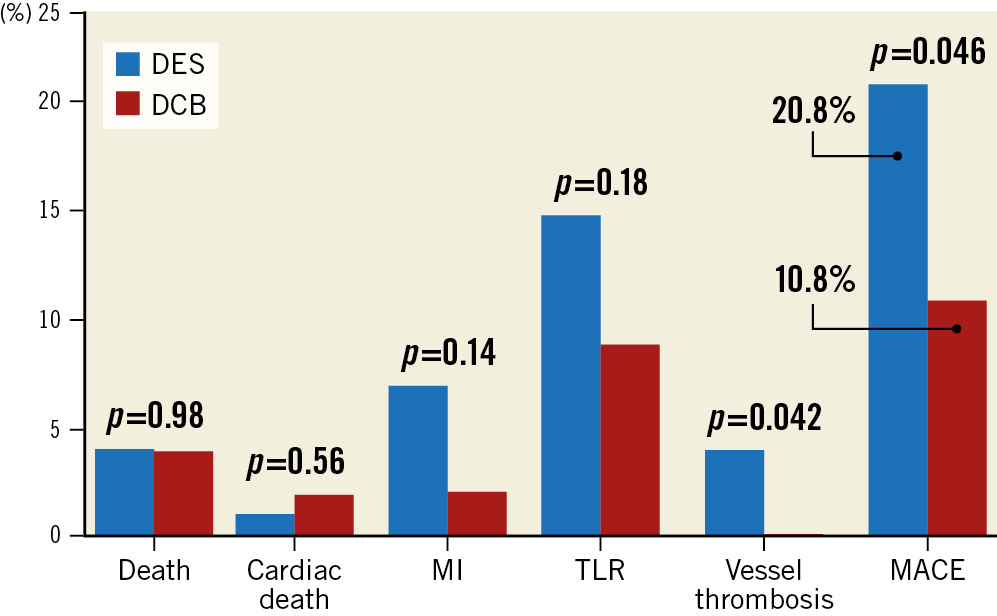

PICCOLETO II is another pivotal study which compared the performance of a novel DCB (ELUTAX SV [AR Baltic Medical]) with an EES (Abbott) in patients with de novo lesions in vessels smaller than 2.75 mm diameter. Six-month in-lesion LLL, the study’s primary endpoint, was significantly higher in the DES arm (0.17±0.39 vs 0.04±0.28 mm; p=0.03 for superiority). At 12-month clinical follow-up, MACE occurred in 7.5% of the DES group and in 5.6% of the DCB group (p=0.55), with a numerically higher incidence of spontaneous MI (4.7% vs 1.9%; p=0.23) and vessel thrombosis (1.8% vs 0%; p=0.15) in the DES arm36. The final follow-up of this study was recently published37. After 3 years, the authors reported a significant reduction in abrupt vessel closure and MACE in the DCB arm (10.8% vs 20.8%; p=0.046) (Figure 1).

Recently, Ahmad published the results of the first-in-human direct comparison of a sirolimus-coated balloon (SCB; SeQuent) with a PCB (SeQuent Please) in 70 patients with coronary de novo lesions38. With similar LLL (0.01±0.33 mm in the PCB group vs 0.10±0.32 mm in the SCB group) at 6-month follow-up, the study met the predefined non-inferiority margin. Interestingly, LLE was more frequently observed after PCB treatment (60% of lesions vs 32% in the SCB group; p=0.019).

In light of these findings, a recent meta-analysis reported the outcomes of DCB versus DES in de novo SVD, including five RCTs (1,459 patients; DCB n=734 and DES n=725)39. Over a 6-month follow-up, the authors found DCB to be associated with lower LLL compared with DES (mean difference â0.12 mm; p=0.01), as well as with a lower risk of MI, and similar risk of MACE, death, TLR, and TVR compared with DES at 1 year. In another meta-analysis, Sanz Sánchez et al included five RCTs comparing DCB with DES with a mean clinical follow-up of 10.2 months. In this study, the use of DCB was found to be associated with a similar risk of TVR (odds ratio [OR] 0.97, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.56-1.68; p=0.92), TLR (OR 1.74, 95% CI: 0.57-5.28; p=0.33), and all-cause death (OR 1.03, 95% CI: 0.14-7.48; p=0.98), with a significantly lower risk of vessel thrombosis (OR 0.12, 95% CI: 0.01-0.94; p=0.04)40.

Table 2. RESTORE SVD study – five-year clinical follow-up results.

| RESTORE DCB (n=113) | RESTORE DES (n=110) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target lesion failure | 8.0 (9) | 7.3 (8) | 0.85 |

| All-cause death | 3.5 (4) | 3.6 (4) | 1.00 |

| Cardiac death | 0.9 (1) | 2.7 (3) | 0.37 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3.5 (4) | 3.6 (4) | 1.00 |

| Target vessel myocardial infarction | 2.7 (3) | 1.8 (2) | 1.00 |

| Any revascularisation | 16.8 (19) | 15.5 (17) | 0.78 |

| Ischaemia-driven revascularisation | 8.8 (10) | 10.0 (11) | 0.77 |

| Data are presented as % (n). DCB: drug-coated balloon; DES: drug-eluting stent; SVD: small vessel disease | |||

Figure 1. Three-year clinical outcomes of the PICCOLETO II trial. DCB: drug-coated balloon; DES: drug-eluting stent; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; MI: myocardial infarction; TLR: target lesion revascularisation

DCB USE IN DE NOVO LARGE VESSELS

With growing evidence to support the safety and efficacy of DCB in de novo large coronary arteries, the use of DCB alone, or as part of a hybrid strategy in combination with DES, is becoming an intriguing alternative to long metallic implantations17.

A recent trial randomised 288 patients with lesions with a reference vessel diameter between 2.25 and 4.00 mm and lesion length ≤30 mm to the SeQuent Please PCB or an EES. The 9-month LLL was −0.19±0.49 mm in the DCB versus 0.03±0.64 mm in the DES arm (p=0.019), while 12-month MACE was similar (2.44% vs 6.33%; p=0.226)41. In another smaller, multicentre, prospective, observational study enrolling 119 patients with de novo coronary lesions in vessels ≥2.75 mm in diameter, a DCB-only strategy also appeared to be safe and effective for both bifurcation and non-bifurcation lesions. Two-year follow-up revealed TLF, TLR, and TVR rates of 4.0%, 3.4%, and 4.2%, respectively42.

One of the explanations for the favourable outcomes of DCB in diffuse coronary disease could come from another study, which evaluated the vessel vasomotor function after DCB43. In this study, the authors reported that the vasomotor response of the treated vessels was similar between the treated segments and angiographically normal segments (p=0.17), supporting the safety of a DCB-only strategy in treating de novo native coronary lesions.

A DCB strategy could be of particular interest for ostial lesions, as they are associated with geographical miss rates of up to 54% and a 3-fold increase in TLR44. A recent retrospective study investigated the role of DCB on 16-month outcomes (TLR, postinterventional lumen gain and LLL) in patients with ostial coronary lesions (27.3% ISR and 72.7% de novo) and reported favourable results, particularly in the subgroup of de novo lesions, as the TLR rate in the de novo group was significantly lower than the ISR group (2.4% vs 50.0%; p<0.001), with no difference in terms of postoperative or follow-up mean lumen diameter (1.76±1.31 mm vs 1.88±0.64 mm; p=0.187)45. In another study, using a propensity score matching analysis, the authors compared a SeQuent Please PCB to a new-generation DES for ostial lesions in the left anterior descending artery46. At 12-month follow-up, the outcomes were similar between the two groups (MACE: 6% vs 6%; p=1.0; TLR: 2% vs 4%; p=0.56), suggesting the feasibility and safety of this stentless approach for ostial lesions of large vessels.

DCB USE IN BIFURCATION LESIONS

Bifurcation lesions represent another attractive scenario for the use of DCB, either alone or as part of a hybrid strategy, such as DES in the main vessel with DCB for the ostial side branch, as it could spare the patient unnecessary stent implantation in this vulnerable anatomical location which frequently leads to geographical miss or a further two-stent strategy.

Two recent meta-analyses that included several RCTs compared DCB with plain old balloon angioplasty for side branch treatment. DCB were associated with lower LLL (mean difference â0.24 mm; p=0.01)47 and lower rates of MACE (OR 0.21, 95% CI: 0.05-0.84; p=0.03)48. However, no differences were found when analysing the individual components of MACE.

In a recent retrospective study on 181 patients, Ikuta et al found that DCB therapy (using SeQuent Please) of the side branch was linked to late lumen gain (LLG) in 71.7% of cases. The authors also compared patients with LLG and those with LLL, showing numerically lower MACE and TLR rates in the LLG group (2.0% vs 7.8%; p=0.11 and 2.0% vs 7.7%; p=0.11)49.

In the specific and delicate case of the left main stem, Liu et al found that a hybrid strategy − using a DCB in the secondary branch in addition to a DES in the main branch − was superior to a two-stent strategy in terms of LLL, both at the side branch ostium (â0.17 mm vs 0.43 mm; p<0.001) and at the proximal main branch (0.09 mm vs 0.17 mm; p=0.037)50.

In another study, directional atherectomy was used prior to DCB treatment of bifurcation lesions (80% left main). A true bifurcation was present in only 14% of cases, so DCBs were mainly used in the main vessel (and in 3.9% of cases in the side branch). Twelve-month follow-up showed good procedural results, with low restenosis (2.3%) and TLR (3.1%) rates, as well as an acceptable rate of target vessel failure (10.9%), driven only by TVR51.

DCB USE IN LONG AND DIFFUSE LESIONS

As previously stated, long metal implants in diffuse coronary disease are associated with higher rates of target vessel failure4. In this setting, DCB alone or in conjunction with stents may represent an attractive alternative to full-stent implantation.

As appealing as it seems, however, dedicated studies of a DCB-only strategy for long lesions are still lacking, although many of the patients included in pivotal studies using DCB had diffuse coronary artery disease, and these devices provided favourable outcomes365253. Recently, the long-term performance of DCB-only versus being part of a blended strategy in diffuse coronary lesions was investigated in 355 patients (360 lesions) and compared to a group of 672 patients (831 lesions) treated with DES alone54. After 3 years of follow-up, no significant differences in TLR and MACE rates were described (7.3% vs 8.3%; p=0.63; and 11.3% vs 13.7%; p=0.32). Of note, similar TLR and MACE rates were observed between the DCB-only and hybrid strategies. What is more, LLL was considerably lower in the DCB group than in the DES arm (0.06±0.61 mm vs 0.41±0.64 mm; p<0.001). Another recently published study retrospectively enrolled 254 patients with multivessel disease that had been successfully treated with DCB alone or in combination with DES and compared them with 254 propensity-matched patients treated with second-generation DES from an important registry. Not only were the number of stents and total stent length significantly reduced by 65.4% and 63.7%, respectively, by using a blended approach, but a lower rate of MACE was also described in the DCB group (3.9% and 11.0%; p=0.002) at 2-year follow-up, thus demonstrating that by reducing stent burden in multivessel CAD efficiently, improved long-term outcomes may be expected55 .

DCB USE IN REAL-WORLD PATIENTS

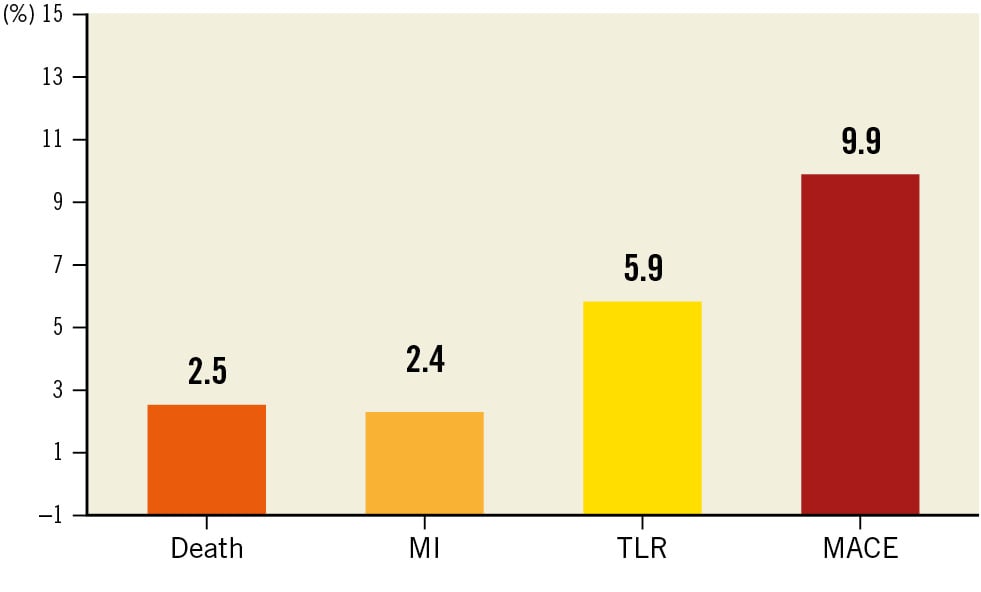

In 2022, the primary endpoint outcome of the largest prospective study on DCB was presented. The EASTBOURNE Registry is an international, investigator-driven study on the performance of MagicTouch SCB in an all-comer population56. The total population enrolled in the 38 centres was 2,123 patients (2,440 lesions), including 44% with ISR, and 45% with complex lesions including acute coronary syndromes (ACS). Interestingly, bailout stenting only occurred in 7% of the patients. After 12 months the primary endpoint of TLR occurred in 5.9% of the lesions, and MACE occurred in 9.9% of the patients. As for paclitaxel DCB, the primary endpoint occurred more frequently in the ISR cohort (10.5% vs 2.0%; risk ratio [RR] 1.90, 95% CI: 1.13-3.19)57. Figure 2 describes the midterm clinical performance of this device.

Figure 2. EASTBOURNE Registry 12-month clinical follow-up. MACE: major adverse cardiac events; MI: myocardial infarction; TLR: target lesion revascularisation

THE ROLE OF DCB IN PATIENTS WITH DIABETES MELLITUS

Diabetes mellitus is a high-risk condition affecting all vascular territories, characterised by diffuse atherosclerotic disease associated with a process of negative remodelling at the coronary site requiring longer and smaller diameter stents. It is well known that the rates of ISR, MI and death are higher in diabetic patients.

Recently, two prospective studies specifically evaluated the safety and efficacy of DCB in this setting5859. As expected, both studies reported that the diabetic group treated with DCB was associated with a higher incidence of 1-year TLF (5.36% vs 2.77%; OR 1.991, 95% CI: 1.077-3.681; 3.9% vs 1.4%; HR 2.712, 95% CI: 1.254-5.864) and TLR (4.15% vs 1.90%; OR 2.233, 95% CI: 1.083-4.602; 2.0% vs 0.5%; HR 3.698, CI: 1.112-12.298) as compared to non-diabetic patients, whereas the rates of MI (OR 4.042, 95% CI: 0.855-19.117; p=0.057; 0.6% vs 0.1%; p=0.110) were not significantly different.

Few studies offer a direct comparison between DCB and DES in diabetic patients. A recent meta-analysis60 including 847 patients from six studies concluded that regarding midterm outcomes (12 months), DCB had significantly lower MACE (RR 0.60, 95% CI: 0.39-0.93), MI (RR 0.42, 95% CI: 0.19-0.94), TLR (RR 0.24, 95% CI: 0.08-0.69), binary restenosis (RR 0.27, 95% CI: 0.11-0.68) and LLL (mean difference â0.31; 95% CI: â0.36 to â0.27).

In a subgroup analysis of the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial61, at the 3-year follow-up, the 252 diabetic DCB patients had lower TVR (9.1% vs 15.0%; p=0.036) as compared to DES patients, along with no significant differences regarding MACE (19.3% vs 22.2%; p=0.51), cardiac death (8.8% vs 5.9%; p=0.16) or non-fatal MI (7.1% vs 9.8%; p=0.24).

A recent subanalysis of the EASTBOURNE study (B. Cortese. Sirolimus coated balloon: expanding the scope of coronary artery disease treatment. Presented at: AICT-AsiaPCR 2022; 6-8 October 2022; Singapore), also showed an adequate performance of the MagicTouch SCB in the diabetic population. Diabetics were 38% of the entire population. Compared to non-diabetic patients, patients with diabetes had non-statistically different TLR at 1 year (6.5% vs 4.2%; p=0.066). However, as in previous studies, diabetic patients had an increased risk of all-cause death (3.5% vs 1.7%; p=0.018), MI (3.5% vs 1.6%; p=0.011) and MACE (11.0% vs 8.1%; p=0.038). The overall incidence of TLR was higher among patients undergoing PCI for ISR as compared to those with de novo coronary lesions; this was independent of diabetic versus non-diabetic status (ISR: 11.7% vs 9.6%; p=0.400; de novo lesions: 2.5% vs 1.8%; p=0.552). The major findings of these studies are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. DCB use in diabetic patients – results from the most recent studies.

| Study | Design | Population | Device | Primary endpoint | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan et al58 | Prospective | 578 diabetic patients | SeQuent Please PCB (B. Braun) | One-year TLF (composite of cardiac death, target vessel MI and TLR) | Higher TLF (5.36% vs 2.77%; OR 1.991; p=0.025) and similar rate of MACE (OR 1.580; p=0.10) in the diabetic group compared to non-diabetic patients |

| Benjamin et al59 | Prospective | 430 diabetic patients | SeQuent Please PCB (B. Braun) | One-year TLF | Higher rate of TLF (3.9% vs 1.4%; p=0.006) among diabetic patients, similar rates of MI (0.6% vs 0.1%; p=0.11) and MACE (4.4% vs 2.7%; p=0.12) when compared to the non-diabetic group |

| Li et al60 | Meta-analysis | 847 diabetic patients (de novo SVD) |

SeQuent Please PCB (B. Braun); IN.PACT PCB (Medtronic); Elutax-SV PCB (Aachen Resonance) | 12-month MACE (composite of MI, TLR, TVR and death) | DCB superior to DES regarding MACE (RR 0.60; p=0.02), occurrence of MI (RR 0.42; p=0.03), TLR (RR 0.24; p<0.001), TVR (RR 0.33; p<0.001), binary restenosis (RR 0.27; p=0.005) and LLL (mean difference –0.31; p<0.001) with respect to midterm (12-month) outcomes; long-term outcomes were similar |

| BASKET-SMALL 261 | Subgroup analysis of RCT | 252 diabetic patients (de novo SVD) |

SeQuent Please PCB (B. Braun) | MACE (composite of cardiac death, non-fatal MI, and TVR) | As compared to DES, DCB was associated with lower rates of TVR (9.1% vs 15.0%; HR 0.4; p=0.036), while MACE, cardiac death and non-fatal MI were similar (19.3% vs 22.2%; HR 0.82; p=0.51; 8.8% vs 5.9%; HR 2.01; p=0.16; 7.1% vs 9.8%; HR 0.55; p=0.24) |

| EASTBOURNE57 | Subgroup analysis of prospective study | 864 diabetic patients | MagicTouch SCB (Concept Medical) | TLR at 12 months | Diabetic patients had similar TLR (6.5% vs 4.2%; p=0.066) and higher rates of all-cause death (3.5% vs 1.7%; p=0.018), MI (3.5% vs 1.6%; p=0.011) and MACE (11.0% vs 8.1%; p=0.038), as compared to non-diabetic patients |

| DCB: drug-coated balloon; DES: drug-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio; LLL: late lumen loss; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; MI: myocardial infarction; OR: odds ratio; PCB: paclitaxel-coated balloon; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SCB: sirolimus-coated balloon; SVD: small vessel disease; TLF: target lesion failure; TLR: target lesion revascularisation; TVR: target vessel revascularisation | |||||

DCB IN HIGH BLEEDING RISK PATIENTS

Another challenging clinical scenario for DES is represented by patients with high bleeding risk (HBR), where potent and prolonged DAPT is risky. In fact, bleeding after PCI has been identified as a strong independent predictor for 1-year mortality in several reports62.

A DAPT duration of 4 weeks following DCB use in de novo lesions has always shown good results in several studies in both stable and acute settings53, and expert consensus documents support this strategy2463. Interestingly, in the case of high-risk patients that require urgent surgery or those with recent bleeding, new evidence shows that the second antiplatelet drug can be omitted after DCB use64.

Recently, a post hoc analysis of 155 HBR patients from the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial was published. Unsurprisingly, HBR was associated with higher mortality rates at 3 years (HR 3.09; p<0.001). While there were no differences in terms of MACE between DCB and DES in the overall population (HR 1.16; p=0.719 vs non-HBR, HR 0.96; p=0.863), DCB showed similar rates of major bleeding in HBR patients (4.5% vs 3.4%) and lower rates in non-HBR patients (0.9% vs 3.8%)65.

DCB IN THE SETTING OF ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

Stent-related events occur more frequently following an ACS, thus, limiting the amount of metal or even a “leave nothing behind” approach seems to be a plausible goal. The efficacy of DCB was recently tested in both ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-STEMI (NSTEMI) patients. Two RCTs found no differences between DCB and DES in the treatment of STEMI patients after 9 months in terms of LLL (0.24±0.39 mm vs 0.31±0.38 mm; p=0.21)66 or fractional flow reserve (0.92±0.05 vs 0.91±0.06)67. The results were consistent at the 2-year follow-up, where similar rates of MACE (5.4% vs 1.9%; HR 2.86, 95% CI: 0.30-27.53; p=0.34) were demonstrated67.

A recent meta-analysis including both STEMI and NSTEMI patients confirmed these results. Between 6 and 12 months of follow-up, there were no differences between the groups regarding the incidence of MACE (RR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.42-1.7) or its individual components. The DCB group was also associated with lower LLL (weighted mean difference â0.29, 95% CI: â0.46 to â0.12)68. Moreover, the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial included 214 patients presenting with an ACS (50% with STEMI). At 1 year, there were lower rates of cardiac death (HR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.15-2.95) and MI (HR 0.00, 95% CI: 0.00-0.32) in the DCB group69.

Future perspectives

Although there are recent data providing more optimistic results regarding the safety and efficacy of DCB in new clinical and angiographic settings, there are still an important number of ongoing trials and studies that should provide further answers regarding the feasibility of DCB as an alternative to metal implantation.

The ISAR-DESIRE5 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05544864) aims to study the difference in the pattern of neointima formation using OCT, following treatment with either the Agent PCB (Boston Scientific) or the XIENCE (Abbott) DES for ISR.

The TRANSFORM I (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03913832)70 trial has randomised patients with SVD (≤2.75 mm) to either the MagicTouch SCB or the SeQuent Please PCB. OCT guidance will allow optimal balloon sizing. The primary endpoint is 6-month in-segment net lumen gain assessed by angiography, and the results will be presented during 2023.

The TRANSFORM II (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04893291)71 trial aims at filling the gap regarding the use of DCB in the treatment of small and medium-sized native coronary artery vessels (2-3 mm) by offering a comparison between MagicTouch DCB and EES in terms of 12-month TLF. Non-inferiority in terms of TLF is hypothesised, whereas a sequential superiority of the DCB arm is expected after the third year and until the final follow-up of the study. The co-primary endpoint of the TRANSFORM II study is net adverse clinical events, which will take into account a potential benefit of DCB in terms of reduction in bleeding due to shorter DAPT duration.

Another study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04664283) aims to evaluate the non-inferiority of DCB compared to DES in the management of large vessel disease (vessel diameter 3.0-4.5 mm), as assessed by OCT. The PRO-DAVID trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04403048) will randomise 650 patients with true bifurcation lesions (including left main) in order to evaluate the impact of the outcome of a hybrid bifurcation approach (DES in the main branch, DCB in the side branch) on 12-month MACE.

The D-Lesion Long Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03155971) will compare a DCB versus a DES approach in patients with long coronary lesions. The primary endpoint is LLL assessed by angiography. Several other studies will address different settings, such as chronic total occlusions (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04744571), various complex lesions (PICCOLETO III), ACS using intravascular ultrasound guidance (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04475978) or HBR patients (DCB-HBR, ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05221931). Pertaining the latter, PREPARE-NSE (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03817801) aims to evaluate the effect of plaque modification using a scoring balloon followed by DCB use in HBR patients, in order to confirm the promising preliminary results from previous studies72.

Conclusions

DCB have the potential to safely and efficiently tackle the limitations of current-era DES in several clinical and technical settings. The last two years have been important in terms of new devices and clinical data for the DCB technology and in “new” angiographic and clinical scenarios, such as large de novo coronary lesions, bifurcations, diffuse CAD, ACS and HBR patients. However, ongoing larger clinical trials with long-term follow-up will be able to validate this approach.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.