Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a life-threatening disorder with high morbidity and mortality. Although percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) technology has improved clinical outcomes in the acute phase, recurrence of coronary events in the chronic phase still occurs at a certain frequency, even after successful initial treatment for ACS123. These events occur at non-culprit lesions with lipid-rich plaques largely because of poor control of coronary risk factors45. Therefore, the strict control of coronary risk factors might improve long-term prognosis after ACS.

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is a well-established causal factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. In a clinical setting, the European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) recommend an LDL-C target of <1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL), or a ≥50% reduction from baseline when this target cannot be reached6. In Japan, strong statins are recommended at the maximum tolerated dose as a class I recommendation in ACS. In high-risk patients whose LDL-C levels do not reach values below 70 mg/dL, even after administration of the maximum tolerated dose of statins, ezetimibe and a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor are considered as class IIa and class IIb recommendations, respectively. In addition, concomitant use of eicosapentaenoic acid with statins may be considered (class IIb recommendation)7.

Despite these recommendations, mortality in the chronic phase after primary PCI for ST-elevation or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI) was reported to have reached a plateau after 20108. One of the reasons might be the insufficient achievement rate of the target LDL-C level in actual clinical settings despite the guideline recommendation910.

Therefore, to implement the optimal lipid-lowering therapy for patients with ACS at our hospital, we started using a hospital lipid-lowering protocol (HLP) of three lipid-lowering drugs. How HLP affects clinical practice and secondary prevention after ACS has not been determined. Thus, the objective of the present study was to elucidate the clinical impact of this HLP after the occurrence of ACS.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

This was a single-centre retrospective observational study. We included 1,803 consecutive patients who underwent successful PCI for ACS between November 2011 and June 2021. Patients not treated with second- or third-generation drug-eluting stents (513 patients) were excluded to eliminate differences in clinical outcomes due to device performance. Patients who developed any event within 90 days (176 patients) which could largely be attributed to the treatment procedure or severity of ACS were also excluded to evaluate the impact of HLP on long-term prognosis. Among the remaining 1,114 enrolled patients, 323 and 791 were included in the HLP and control groups, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1).

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kansai Rosai Hospital (approval no.: 21D012g). Due to the retrospective nature of the study (observational research), written informed consent from patients was not required, in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects in Japan. Instead, relevant information regarding the study was made available to the public, and opportunities for individuals to refuse the inclusion of their data were ensured.

INTERVENTION PROCEDURE

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had ACS with significant stenosis or occlusion on the initial coronary angiography and underwent PCI. PCI and post-PCI management, including antiplatelet therapy, were standardised. Intravenous heparin (5,000 IU), oral aspirin (200 mg), prasugrel (20 mg), and clopidogrel (300 mg) were administered before the PCI procedure. After PCI, all patients received prasugrel (3.75 mg) or clopidogrel (75 mg) once daily in addition to aspirin (100 mg) for the optimal duration in accordance with the relevant guidelines1112.

HLP FOR INTENSIVE LIPID-LOWERING THERAPY

The HLP included the prescription of the maximum tolerated dose of statins, ezetimibe (10 mg), and eicosapentaenoic acid (1,800 mg) daily after successful PCI for patients with ACS during hospitalisation. The order, timing, and initial dose of the three types of lipid-lowering agents were at the chief physician’s discretion. Protocol compliance was defined as the prescription of those three drugs at discharge. If the patient’s LDL-C level was >1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) one month after HLP initiation, a PCSK9 inhibitor was recommended. Since HLP was only recommended, the final decision for its prescription was decided by the chief physician based on the patient’s status.

OUTCOME MEASURES

We compared the 2-year clinical outcomes before (control group) and after (HLP group) the introduction of HLP for intensive lipid-lowering therapy. The primary outcome measure was the 2-year cumulative incidence of non-target vessel revascularisation (non-TVR). The secondary outcome measures were major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as a composite of cardiac death, MI, any repeat revascularisation, and stent thrombosis, and other clinical outcomes, including all-cause death, cardiac death, MI, target lesion revascularisation (TLR), TVR, and definite stent thrombosis (defined in Supplementary Appendix 1). The achievement rate of LDL-C <1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) and the change in LDL-C at 1 year were also evaluated.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

All results are expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise stated. Continuous variables with and without homogeneity of variance were analysed using the Student’s t-test and Welch’s t-test, respectively. Categorical variables were analysed using Fisher’s exact test for 2×2 comparisons. For more than 2×2 comparisons, nominal and ordinal variables were analysed using the chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Clinical outcomes were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared before and after HLP introduction using the log-rank test. To minimise intergroup differences in baseline characteristics, a multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model and inverse probability weighting (IPW) based on the propensity score for the protocol were used to evaluate the effects of the protocol on the outcomes while adjusting for covariates including age, sex, left ventricular ejection fraction, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, current smoking, chronic kidney disease, haemodialysis, chronic heart failure, stroke, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, type of ACS, ostial lesion, bifurcation, moderate-severe calcification, ACC/AHA classification, in-stent restenosis, average stent size, total stent length, lesion location, and number of stents. To confirm the robustness of these results, we performed an analysis with IPW based on the propensity score for the protocol. A logistic regression model was applied to predict the probability of the protocol using the covariates as stated for the Cox proportional hazard regression model. The results of the model were presented as adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI). All tests were two-sided with a 5% significance level. All calculations were performed using the SPSS Statistics package, version 28.0J (IBM) and R software, version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

The patient, lesion, and procedural characteristics are summarised in Table 1. In terms of coronary risk factors, hypertension (64% vs 78%; p<0.001) and haemodialysis (9% vs 14%; p=0.047) were more frequent in the control group. Lesion complexities, including bifurcation (47% vs 39%; p=0.009) and moderate-severe calcification (20% vs 16%; p=0.047), were more severe in the HLP group than in the control group.

Table 1. Patient, lesion, and procedural characteristics.

| Patient characteristics | HLP group (n=323) | Control group (n=791) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 237 (73) | 595 (75) | 0.57 |

| Age, yrs | 73 (62-80) | 71 (62-78) | 0.15 |

| LVEF, % | 58 (49-65) | 61 (50-67) | 0.058 |

| Hypertension | 208 (64) | 614 (78) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 212 (66) | 474 (60) | 0.066 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 125 (39) | 286 (36) | 0.40 |

| Current smoker | 79 (24) | 162 (20) | 0.14 |

| CKD | 59 (18) | 180 (23) | 0.10 |

| Haemodialysis | 30 (9) | 108 (14) | 0.047 |

| CHF | 22 (7) | 59 (7) | 0.72 |

| Stroke | 10 (3) | 46 (6) | 0.061 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 27 (8) | 51 (6) | 0.25 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 20 (6) | 78 (10) | 0.051 |

| Type of ACS on admission | 0.72 | ||

| STEMI | 136 (42) | 308 (39) | |

| NSTEMI | 49 (15) | 83 (10) | |

| UAP | 137 (43) | 400 (51) | |

| Lesion characteristics | HLP group (n=378) | Control group (n=927) | p-value |

| Lesion location | 0.77 | ||

| Left anterior descending artery | 160 (42) | 365 (39) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 73 (19) | 204 (22) | |

| Right coronary artery | 131 (35) | 333 (36) | |

| Left main trunk | 11 (3) | 19 (2) | |

| Bypass graft | 2 (1) | 6 (1) | |

| In-stent restenosis | 20 (5) | 71 (8) | 0.13 |

| Ostial lesion | 46 (12) | 138 (15) | 0.21 |

| Bifurcation | 176 (47) | 360 (39) | 0.009 |

| Moderate-severe calcification | 77 (20) | 147 (16) | 0.047 |

| ACC/AHA classification | 0.22 | ||

| Type A | 2 (1) | 11 (1) | |

| Type B1 | 68 (18) | 174 (19) | |

| Type B2 | 48 (13) | 151 (16) | |

| Type C | 259 (68) | 591 (64) | |

| Procedural characteristics | HLP group (n=378) | Control group (n=927) | p-value |

| Aspiration | 146 (42) | 723 (49) | 0.034 |

| Distal protection | 18 (5) | 191 (13) | <0.001 |

| Predilatation | 261 (69) | 1671 (72) | 0.25 |

| Predilatation balloon size, mm | 2.5 (2.0-3.0) | 2.5 (2.25-3.0) | 0.61 |

| No. of stents | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 0.084 |

| Average stent size, mm | 3.0 (2.5-3.5) | 3.0 (2.6-3.5) | 0.62 |

| Total stent length, mm | 28 (18-38) | 24 (18-38) | 0.001 |

| Post-dilatation | 360 (95) | 770 (83) | <0.001 |

| Post-dilatation balloon size, mm | 3.5 (3.0-4.0) | 3.25 (3.0-3.5) | <0.001 |

| Type of stent | <0.001 | ||

| XIENCE1 | 145 (38) | 333 (36) | |

| Nobori2 | 0 (0) | 37 (4) | |

| PROMUS3 | 0 (0) | 69 (7) | |

| Resolute4 | 10 (3) | 81 (9) | |

| SYNERGY3 | 14 (4) | 171 (18) | |

| Ultimaster2 | 6 (2) | 129 (14) | |

| Orsiro5 | 95 (25) | 56 (6) | |

| BioFreedom6 | 39 (10) | 51 (6) | |

| COMBO Plus7 | 21 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Coroflex ISAR NEO8 | 47 (12) | 0 (0) | |

| Data are presented as medians (interquartile ranges) or numbers (%). 1By Abbott; 2by Terumo; 3by Boston Scientific; 4by Medtronic; 5by Biotronik; 6by Biosensors; 7by OrbusNeich; 8by B. Braun.ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CHF: chronic heart failure; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DCB: drug-coated balloon; HLP: hospital lipid-lowering protocol; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UAP: unstable angina pectoris | |||

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

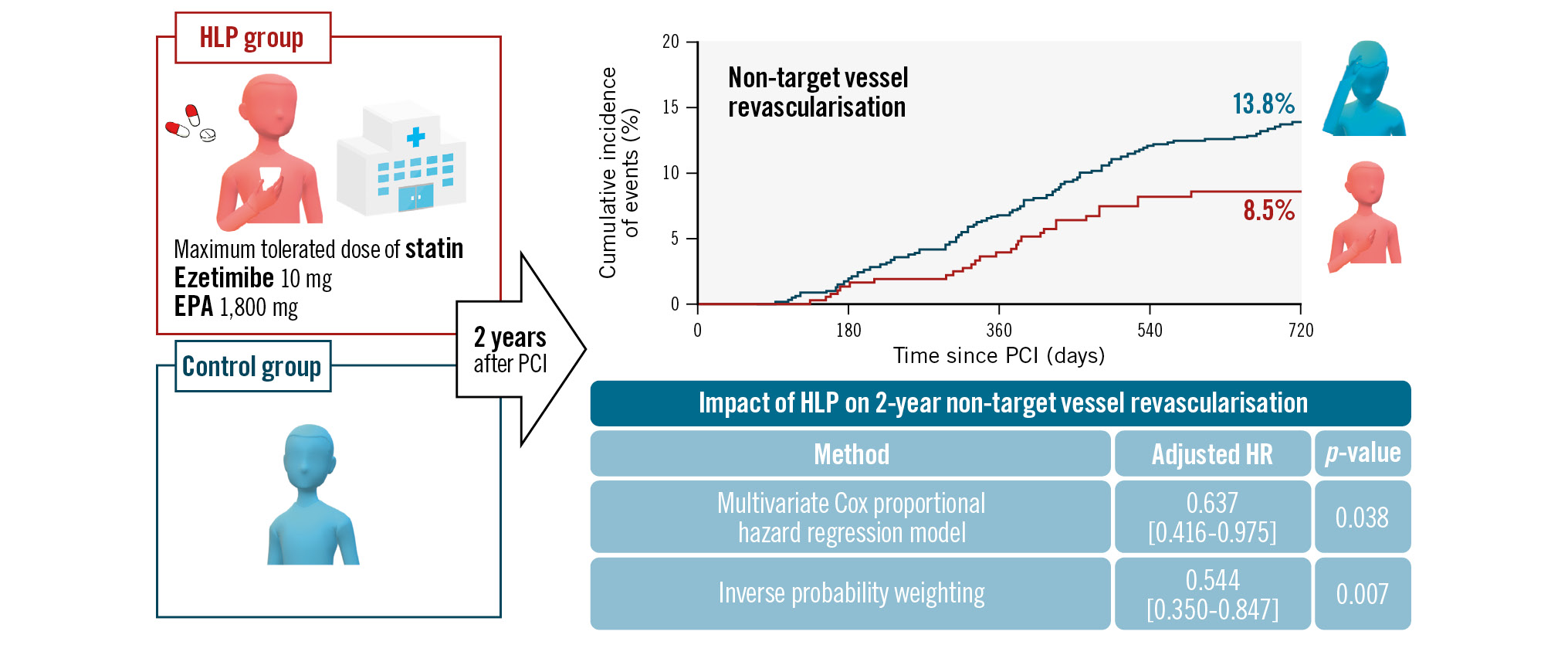

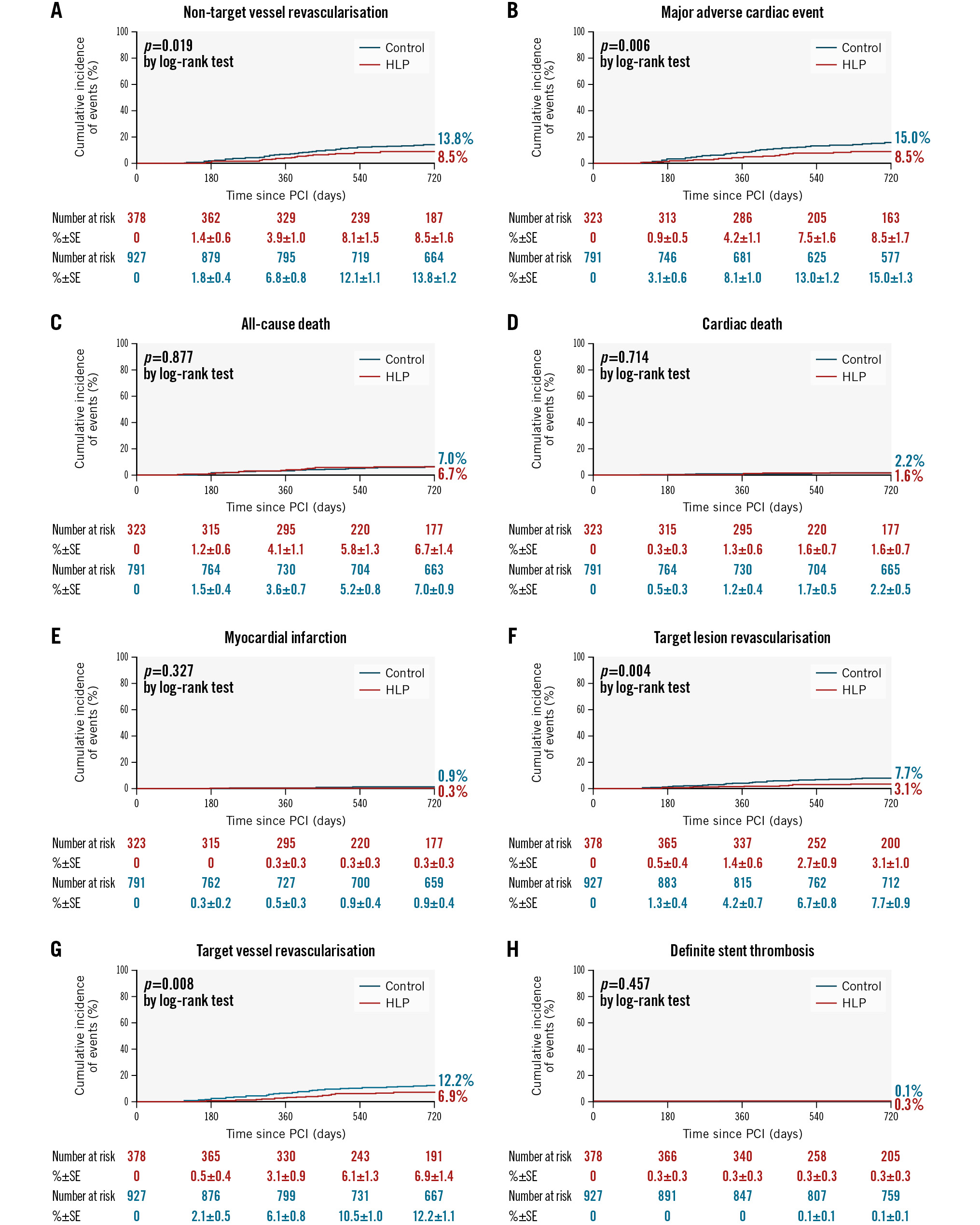

The Central illustration and Figure 1 show the cumulative incidence of each outcome and its Kaplan-Meier curve. After adjusting for covariates using a multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model, the cumulative incidences of non-TVR (adjusted hazard ratio 0.637, 95% CI: 0.416-0.975; p=0.038), as well as those of TLR and TVR, were still significantly lower in the HLP group (Table 2). The IPW analysis consistently showed a significantly lower risk of non-TVR in the HLP group (adjusted hazard ratio 0.544, 95% CI: 0.350-0.847; p=0.007).

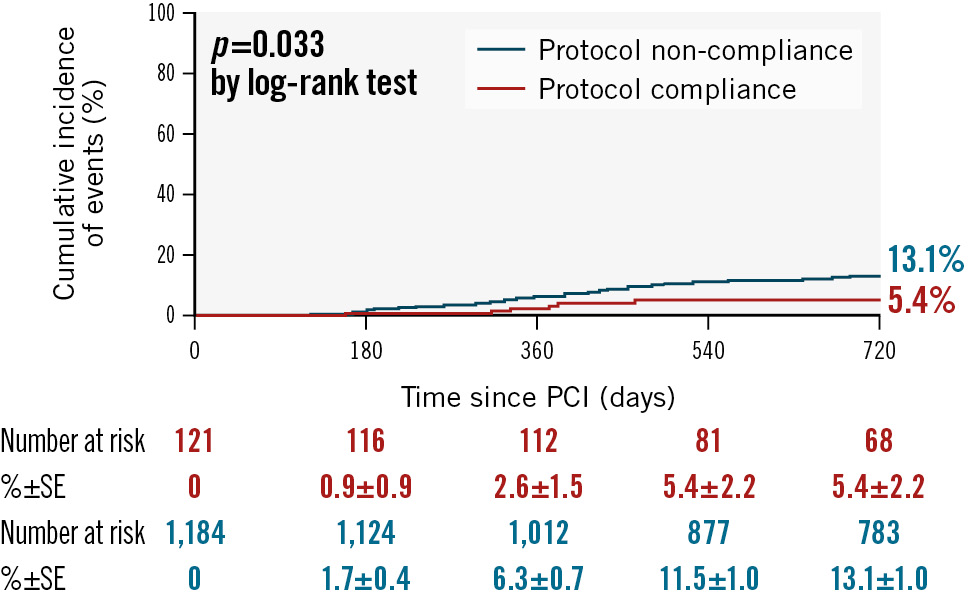

To demonstrate the efficacy of protocol compliance, we further analysed whether HLP compliance had an impact on clinical outcomes. Compared to the protocol non-compliance group, non-TVR (5.4% vs 13.1%; p=0.033) was significantly lower in the protocol compliance group (Figure 2).

Central illustration. A hospital lipid-lowering protocol (HLP) improves 2-year clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. A hospital lipid-lowering protocol improved the cumulative 2-year incidence of non-target vessel revascularisation in patients with acute coronary syndrome. EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; HR: hazard ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence rates of 2-year clinical outcomes. A) Non-target vessel revascularisation: hospital lipid-lowering protocol (HLP) 8.5%, control 13.8% (p=0.019). B) Major adverse cardiac events: HLP 8.5%, control 15.0% (p=0.006). C) All-cause death: HLP 6.7%, control 7.0% (p=0.877). D) Cardiac death: HLP 1.6%, control 2.2% (p=0.714). E) Myocardial infarction: HLP 0.3%, control 0.9% (p=0.327). F) Target lesion revascularisation: HLP 3.1%, control 7.7% (p=0.004). G) Target vessel revascularisation: HLP 6.9%, control 12.2% (p=0.008). H) Definite stent thrombosis: HLP 0.3%, control 0.1% (p=0.457). PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SE: standard error

Table 2. Cumulative incidence of each clinical outcome after adjusting for covariates by a multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model and IPW.

| Crude | Multivariate | IPW | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | p-value | HR | p-value | HR | p-value | |

| Non-TVR | 0.614 [0.406-0.927] | 0.019 | 0.637 [0.416-0.975] | 0.038 | 0.544 [0.350-0.847] | 0.007 |

| MACE | 0.544 [0.350-0.845] | 0.006 | 0.721 [0.508-1.024] | 0.068 | 0.795 [0.540-1.171] | 0.246 |

| All-cause death | 0.959 [0.568-1.622] | 0.742 | 0.960 [0.536-1.722] | 0.892 | 1.00 [0.577-1.737] | 0.998 |

| Cardiac death | 0.829 [0.303-2.266] | 0.714 | 0.567 [0.177-1.813] | 0.339 | 1.01 [0.348-2.944] | 0.982 |

| MI | 0.366 [0.045-2.974] | 0.327 | 0.086 [0.003-2.153] | 0.135 | 0.870 [0.111-6.843] | 0.894 |

| TLR | 0.389 [0.200-0.756] | 0.004 | 0.441 [0.223-0.873] | 0.019 | 0.720 [0.324-1.600] | 0.419 |

| TVR | 0.542 [0.342-0.858] | 0.008 | 0.623 [0.389-0.997] | 0.049 | 0.829 [0.486-1.413] | 0.490 |

| ST | 2.745 [0.171-44.071] | 0.457 | 2.220 [0.000-1.328] | 0.988 | 1.504 [0.106-21.290] | 0.763 |

| P-values in bold indicate statistical significance. HR: hazard ratio; IPW: inverse probability weighting; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; MI: myocardial infarction; non-TVR: non-target vessel revascularisation; ST: stent thrombosis; TLR: target lesion revascularisation; TVR: target vessel revascularisation | ||||||

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence of 2-year clinical outcomes stratified by hospital lipid-lowering protocol compliance. Non-target vessel revascularisation: protocol compliance group 5.4%, protocol non-compliance group 13.1% (p=0.033). PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SE: standard error

LIPID PROFILES

The patients’ lipid profiles at the index PCI and 1 year afterwards are provided in Supplementary Table 1. The 1-year achievement rate of LDL-C <1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) reached 61% in the HLP group, which was significantly higher than that in the control group (27%; p<0.001). Details of the prescription of lipid-lowering drugs, including the type and dose of statins, and side effects are provided in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3.

Discussion

The results of our retrospective analyses of more than 1,100 patients who underwent successful PCI for ACS at our hospital demonstrated that the cumulative incidence rates of non-TVR, TLR, and TVR at 2 years were significantly lower after HLP introduction according to multivariate analyses. The IPW analysis confirmed the effectiveness of HLP in non-TVR events.

HLP AND CARDIOVASCULAR EVENTS

Non-TVR events occasionally occur, even after successful PCI for non-culprit stenotic lesions in patients with ACS. The results of the FLOWER-MI study suggest that the plaque in non-culprit lesions is highly unstable, and revascularisation by functional ischaemia evaluation alone is insufficient to prevent cardiovascular events after ACS treatment13. Therefore, stabilising unstable lipid plaques in lesions not responsible for ACS by strict lipid-lowering therapy is especially important in preventing non-TVR events. High-potency statins at the maximum tolerable dose have been recommended as the cornerstone lipid-lowering therapy and were reported to significantly reduce the plaque volumes of non-culprit lesions in patients with ACS14. In addition, the combination of statin plus ezetimibe or eicosapentaenoic acid showed greater coronary plaque regression compared to standard statin monotherapy151617. Furthermore, alirocumab, a PCSK9 inhibitor, made the fibrous cap thicker, the lipid plaque angle smaller, and the atheroma volume smaller as evaluated by intravascular imaging compared to placebo, which were significant effects18. Regarding the timing of the introduction of these drugs, early aggressive lipid-lowering therapy after ACS significantly reduced the plaque volume of non-culprit lesions in patients with ACS19. Due to these plaque-stabilising effects of lipid-lowering drugs, early lipid-lowering therapy with statins decreases not only short-term mortality but also recurrent cardiovascular events2021. Our present analyses revealed that after HLP introduction, prescription rates of high-potency statins, ezetimibe, and eicosapentaenoic acid at discharge increased to 90%, 63%, and 41%, respectively. HLP helped accomplish the early introduction of intensive lipid-lowering therapy including the maximum tolerated dose of higher-potency statins, concomitantly used with ezetimibe and eicosapentaenoic acid. These factors have contributed to increasing the achievement rate of LDL-C <1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) to 61%, resulting in reduced non-TVR rates. A subanalysis confirmed the effectiveness of our HLP (Figure 2).

IMPROVEMENT OF 2-YEAR CLINICAL OUTCOMES

Previously, we reported 1-year results after the introduction of HLP showing that HLP did not decrease clinical adverse events, while the achievement rate of the target LDL-C level significantly improved22. The Kaplan-Meier curves of previous studies, in which lipid-lowering drugs improved clinical outcomes, demonstrate that the difference in event rates between the HLP group and the control group increases after 1 year202324. Therefore, long-term follow-up is necessary to demonstrate the efficacy of lipid-lowering therapy, and it is considered that at least 2 years are necessary for our HLP to improve clinical outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically demonstrate the efficacy of HLP for intensive lipid-lowering therapy to achieve the target LDL-C level and improve real-world clinical outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was a single-centre retrospective observational study, and the two groups showed heterogeneity in both baseline demographic and procedural variables; however, we matched the baseline characteristics with multivariate Cox regression analysis, as well as IPW analysis based on propensity scores. Second, the proportion of HLP-compliant patients was low, at 32%, possibly because the introduction of lipid-lowering drugs depended on the physician, and higher age and unstable angina were considered independent predictors of poor HLP compliance as previously reported22. However, HLP-compliant patients showed better clinical outcomes (Figure 2), and the clinical improvement is still recognised even though the HLP compliance rate is relatively low. Therefore, further improvement in clinical results can be expected by increasing the HLP compliance rate. Third, there might be a difference in the frequency of follow-up angiography and non-clinically driven revascularisation because no clinical benefits were observed for routine follow-up coronary angiography after PCI. However, patients who underwent follow-up coronary angiography for any reason accounted for 43% (343/791) before and 43% (138/323) after HLP introduction, which showed no significant difference. Fourth, 2-year data about LDL-C values and prescribed lipid-lowering drugs are rare, and we could not demonstrate a direct relationship between LDL-C values and clinical outcomes. Furthermore, we could not evaluate the patients’ medication compliance, and medication use may have been overestimated. Finally, TLR and TVR rates were not significantly different in the IPW analysis, in contrast to the multivariate analysis. The relatively low number of events might be the reason, and the longer follow-up and higher number of events might have made a difference in the IPW analysis.

Conclusions

Implementing HLP for patients with ACS who underwent successful PCI improved the 2-year clinical outcomes including non-TVR in multivariate analyses, and the IPW analysis confirmed the effectiveness of HLP for non-TVR.

Impact on daily practice

A hospital lipid-lowering protocol (HLP) that includes the prescription of the maximum tolerated dose of statin, ezetimibe, and eicosapentaenoic acid could increase the achievement rate of the guideline-directed low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and reduce 2-year cardiovascular events for patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). It is strongly recommended to implement an in-hospital protocol for lipid-lowering therapy after ACS. Since the proportion of HLP compliance was still low, further improvement of clinical results can be expected by striving to increase the HLP compliance rate. In addition, longer-term follow-up is necessary to confirm the effectiveness of HLP.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Ms Saori Kashu for her expertise in data aggregation.

Conflict of interest statement

T. Ishihara received lecture fees from Nipro and Kaneka. O. Iida received remuneration from Boston Scientific Japan, W. L. Gore & Associates G.K., BD, and Terumo. T. Mano received a research grant from Abbott Vascular Japan. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.