Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor) is the standard of care for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stents (DES)1,2. However, the optimal duration of DAPT remains a topic of debate3, particularly in complex lesions.

Patients with a coronary bifurcation account for 15-20% of candidates to PCI and are at higher risk of both periprocedural and long-term adverse events4. Coronary artery bifurcation lesions exhibit localised turbulent flow and an enhanced propensity for platelet aggregation, plaque rupture, and atherothrombosis. Anatomical factors, including the fractal geometry of vascular bifurcations, increase the incidence of strut malapposition and stent underexpansion. Definite or probable stent thrombosis (ST) occurs more frequently early (within the first 30 days) rather than late. The overall incidence of ST in bifurcation PCI is in the range of 1.5-2%, almost double as compared to non-bifurcation PCI (<1%)4. The risk varies according to bifurcation complexity, as ST occurs in about 2% when side branch (SB) lesion length is >10 mm, and 1% for SB lesion length <10 mm5, and procedural technique, with two stents showing a doubled risk of ST as compared to a single-stent technique6.

The term “bifurcation lesion” encompasses a large variety of anatomic subsets and clinical scenarios, from left main (LM) bifurcation with a significant amount of myocardium at risk to a small branching lateral branch with negligible myocardium at risk. Such anatomic subsets, both listed in the “complex bifurcation lesion” classification of the DEFINITION II study7 (Supplementary Table 1), show thrombotic and ischaemic risks pointing in different directions, therefore hindering the identification of the optimal antithrombotic therapy.

The European Bifurcation Club (EBC) recommends single stenting with the “provisional” side branch (SB) stenting strategy for the treatment of the vast majority of bifurcation lesions6, while European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines “suggest considering” the use of double stenting with the double kissing (DK-) crush technique in the treatment of LM bifurcation lesions (class IIb, level of evidence [LOE] B), following the results of the DKCRUSH-V trial8.

In any event, careful planning is absolutely mandatory in bifurcation PCI, as a “bail-out” placement of a second stent has been associated with higher risk of ST than planned double stenting9,10.

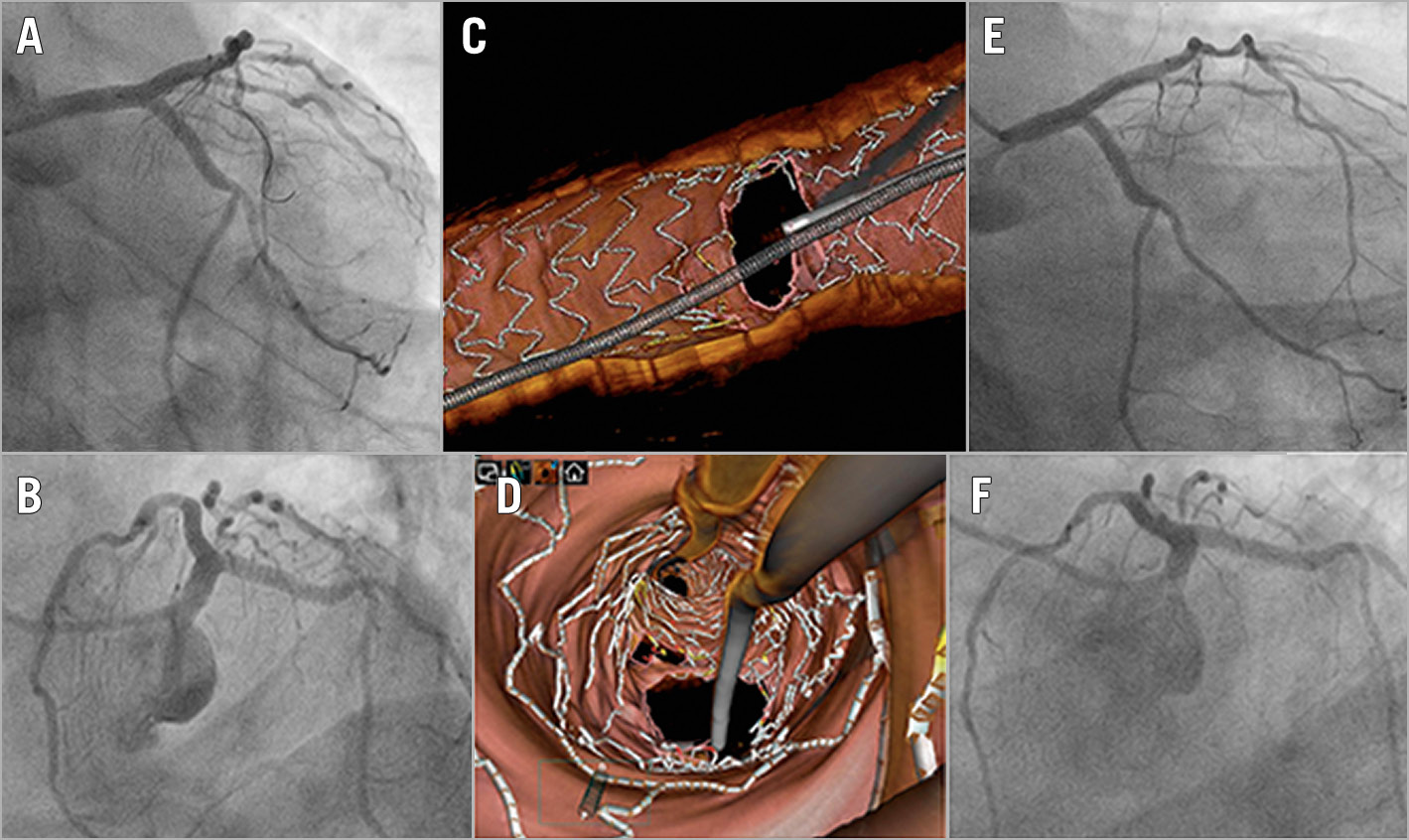

In the two-stent strategy, the EBC recommends final kissing balloon inflation followed by the proximal optimisation technique (POT) in order to minimise strut malapposition and subsequent ST risk6. Intravascular guidance represents a valuable strategy in bifurcation PCI: ESC guidelines recommend intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guidance only for the treatment of unprotected LM lesions (class IIa, LOE B)11, while the EBC underlines the benefit of intravascular imaging for any bifurcation6 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. OCT assessment of LM bifurcation stenting. After double stenting of the left main (LM) with the culotte technique (A & B), 3D optical coherence tomography (OCT) documented adequate stent expansion without strut protrusion (C & D). The patient remained asymptomatic and, 12 months later, the stents were widely patent at control angiography (E & F).

Therefore, the implementation of individualised antithrombotic management to mitigate the risk of ST and spontaneous myocardial infarction (MI) without a concurrent increased risk of bleeding according to the procedural complexity in PCI bifurcation answers a clinical need.

The EBC suggested a state-of-the-art paper on antithrombotic therapy after bifurcation PCI. The document chairs (M. Zimarino and D.J. Angiolillo) identified key opinion leaders from Europe, America, and Asia with expertise in basic, translational, and clinical sciences in the field of antiplatelet therapy and interventional cardiology.

In this manuscript, specific issues related to antithrombotic therapy after PCI of bifurcation lesions are presented. For further details please refer to Supplementary Appendix 1.

CHOICE OF ANTITHROMBOTIC DRUGS AND TIMING OF INITIATION

In acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients, potent oral P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel and ticagrelor) are recommended in the light of their superior efficacy when compared to clopidogrel2. As compared to clopidogrel, ticagrelor12 and prasugrel13 were associated with a similar (1.0% and 1.2%, respectively) absolute reduction of ST in ACS patients, which was higher (3.2% after prasugrel) in the cohort of patients with a bifurcation stent13. Following the results of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial14, ESC guidelines15 now give a preference to prasugrel over ticagrelor in patients who proceed to PCI (class IIa).

Although the efficacy of newer P2Y12 inhibitors over clopidogrel has never been documented in stable coronary artery disease (CAD), the authors agree with the ESC guidelines, where prasugrel and ticagrelor may be considered (class IIb) in patients with stable CAD and a high risk of thrombosis, such as complex LM cases, based on expert consensus (LOE C)16.

With ST occurring mostly in the acute and early phase, rapid and effective i.v. inhibition of the platelet P2Y12 receptor may be adopted in patients undergoing bifurcation PCI without adequate pretreatment. A substudy of the CHAMPION-PHOENIX trial reported that the number of high-risk lesions (a coronary bifurcation was present in almost 50% of cases) was strongly predictive of periprocedural MI and ST and cangrelor significantly reduced such adverse events, with a greater absolute effect proportional to the number of high-risk lesions, irrespective of clinical presentation17.

DAPT DURATION AND RISK STRATIFICATION

International guidelines list coronary bifurcation as a risk factor for ST (among other characteristics of PCI complexity), suggesting that a longer duration of DAPT for both stable CAD and ACS may be considered in this setting (class IIb, LOE B)1,2.

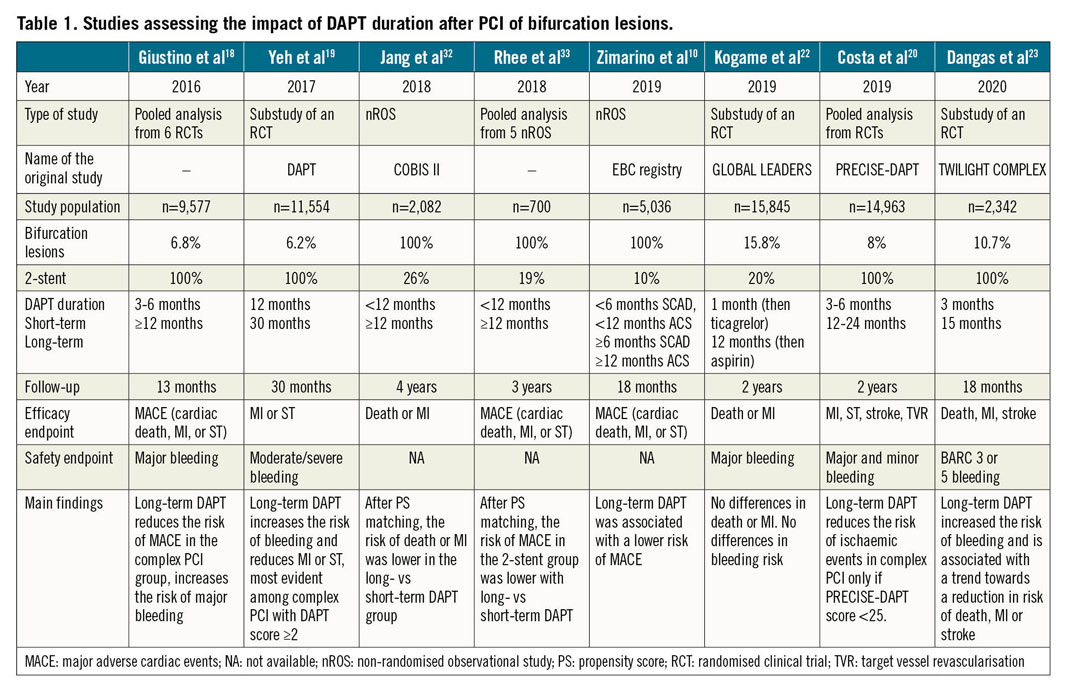

This recommendation is based mainly on a meta-analysis18 (Table 1) where, as compared with 3-6 months, ≥12 months DAPT duration was associated with a significant reduction in the composite endpoint among patients who underwent “complex” PCI – defined according to the so-called “Giustino criteria” – but not in the non-complex PCI group (pinteraction = 0.01). The presence of a bifurcation treated with double stenting was the strongest risk factor for the composite of cardiac death, MI or ST, and its individual components. Long-term DAPT was associated with an increased risk for major bleeding, regardless of PCI complexity.

Given the trade-off between ischaemic and bleeding risks for any DAPT duration, three scoring systems have been developed (Supplementary Table 2).

A substudy of the DAPT trial19 (Table 1) documented that, among subjects with anatomic complexity (19% double stenting for bifurcation), those with a DAPT score ≥2 receiving 30-month DAPT experienced a significantly lower rate of MI or ST (3.0%) than those receiving only 12-month DAPT (6.1%, p<0.001), while no difference was detected among patients with a score <2.

In a sub-analysis of the PRECISE-DAPT pooled data set20 (Table 1), patients who underwent a complex PCI, based on the Giustino criteria18, experienced a risk reduction (-4%) in the composite net adverse clinical events from long-term DAPT only if the bleeding risk at baseline was low (PRECISE-DAPT score <25). When receiving long-term DAPT, patients at high baseline bleeding risk (PRECISE-DAPT score ≥25) experienced no significant risk reduction for ischaemic events regardless of the complexity of PCI and suffered a significant excess of bleeding complications (pint=0.89).

The greatest benefit of prolonged DAPT is accrued in bifurcation PCI with a larger thrombogenic milieu (ACS, double stenting, no imaging) and higher ischaemic risk (large myocardium at risk, as for unprotected LM); in this setting, a thorough evaluation of the bleeding risk becomes crucial.

THE IDENTIFICATION OF PATIENTS AT HIGH BLEEDING RISK

The concept of “high bleeding risk” (HBR) has recently been emphasised to guide DAPT duration in patients undergoing PCI2.

The Academic Research Consortium (ARC)-HBR initiative recently issued a consensus21 identifying HBR patients as those with a one-year risk of a Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC)-defined type 3 or 5 bleeding of ≥4% and of intracranial haemorrhage of ≥1%. According to twenty clinical major or minor criteria (Supplementary Table 3), patients are identified as being at HBR if at least one major criterion or two minor criteria are met.

In the context of bifurcation PCI, the identification of HBR should be an argument to favour a procedural strategy – single “provisional” stenting, intravascular guidance – that allows a shorter DAPT duration.

ROLE OF P2Y12-RECEPTOR INHIBITOR MONOTHERAPY

Against the tenet of P2Y12 inhibitor discontinuation on a background of continued aspirin, there has been growing interest in the concept of discontinuing aspirin in favour of monotherapy with a sole P2Y12 inhibitor, aiming to contain the bleeding risk.

In the GLOBAL LEADERS trial, among patients who underwent bifurcation PCI (16%) with a biolimus-eluting stent (Table 1), one month of DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months was associated with a similar risk of two-year all-cause death or MI, without any significant reduction in the bleeding risk when compared with 12-month DAPT followed by aspirin22.

In the TWILIGHT-COMPLEX substudy23 (Table 1), this approach was specifically evaluated among patients who underwent “complex” PCI, with two-stent bifurcation being used in 10.7% of cases. Ticagrelor monotherapy was associated with a similar and consistent reduction in the BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding risk in both the “complex” and “non-complex” PCI groups, without increasing the risk of ischaemic events.

A recent meta-analysis documented that ST was infrequent, and aspirin discontinuation was not associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk24. However, such an appealing strategy still needs confirmation in the bifurcation setting.

SWITCHING OR DISCONTINUATION OF P2Y12 INHIBITORS

In general, escalation – an increase in platelet inhibition – may be indicated in the early phase after a complex PCI25. The presence of high-risk angiographic characteristics, namely thrombotic, long, and bifurcating lesions, has been identified as the major determinant of escalation from clopidogrel to prasugrel in clinical practice26.

De-escalation – the transition from a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor – is the most common of the switching strategies, given that thrombotic events are more likely to occur early and the prolonged use of potent P2Y12 inhibition is associated with an increased risk of bleeding with less enhanced antithrombotic benefit25. It comes into the clinical field when you have, for example, a high-risk lesion such as in bifurcation stenting but at the same time an HBR on ticagrelor or prasugrel.

Premature discontinuation of oral antiplatelet therapy after PCI is associated with a significant increase in the risk of ischaemic events and ST27, with non-cardiac surgery representing one of the most common causes.

Following the Surgery After Stenting 2 document28, bridging with an intravenous antiplatelet agent, such as cangrelor at a dose regimen of 0.75 mcg/kg/min, may be recommended in patients deemed to be at high thrombotic risk, such as those with bifurcation lesions treated with double stenting, who cannot safely interrupt oral antiplatelet therapy.

MANAGEMENT OF CANDIDATES FOR ORAL ANTICOAGULATION

A recent meta-analysis29 underlined that, in candidates for oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy after PCI, a dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT) with OAC and a single antiplatelet agent is associated with a reduction of bleeding as compared with triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT, i.e., OAC in combination with DAPT) (risk ratio [RR] 0.66, 95% CI: 0.56-0.78; p<0.0001); non-vitamin K (N)OAC-based DAT versus vitamin K antagonist TAT yielded consistent results and a significant reduction of intracranial haemorrhage (RR 0.33, 95% CI: 0.17-0.65; p=0.001). Such benefit is, however, counterbalanced by a significant increase of ST (RR 1.59, 95% CI: 1.01-2.50; p=0.04) and a trend towards higher risk of MI with DAT as compared with TAT.

Substudies on complex lesions from both the PIONEER AF-PCI trial30 and the REDUAL PCI trial31 showed that NOAC-based DAT following PCI was associated with a reduced bleeding and a similar thrombotic risk compared with warfarin-based TAT, irrespective of the complexity of PCI.

Conclusions

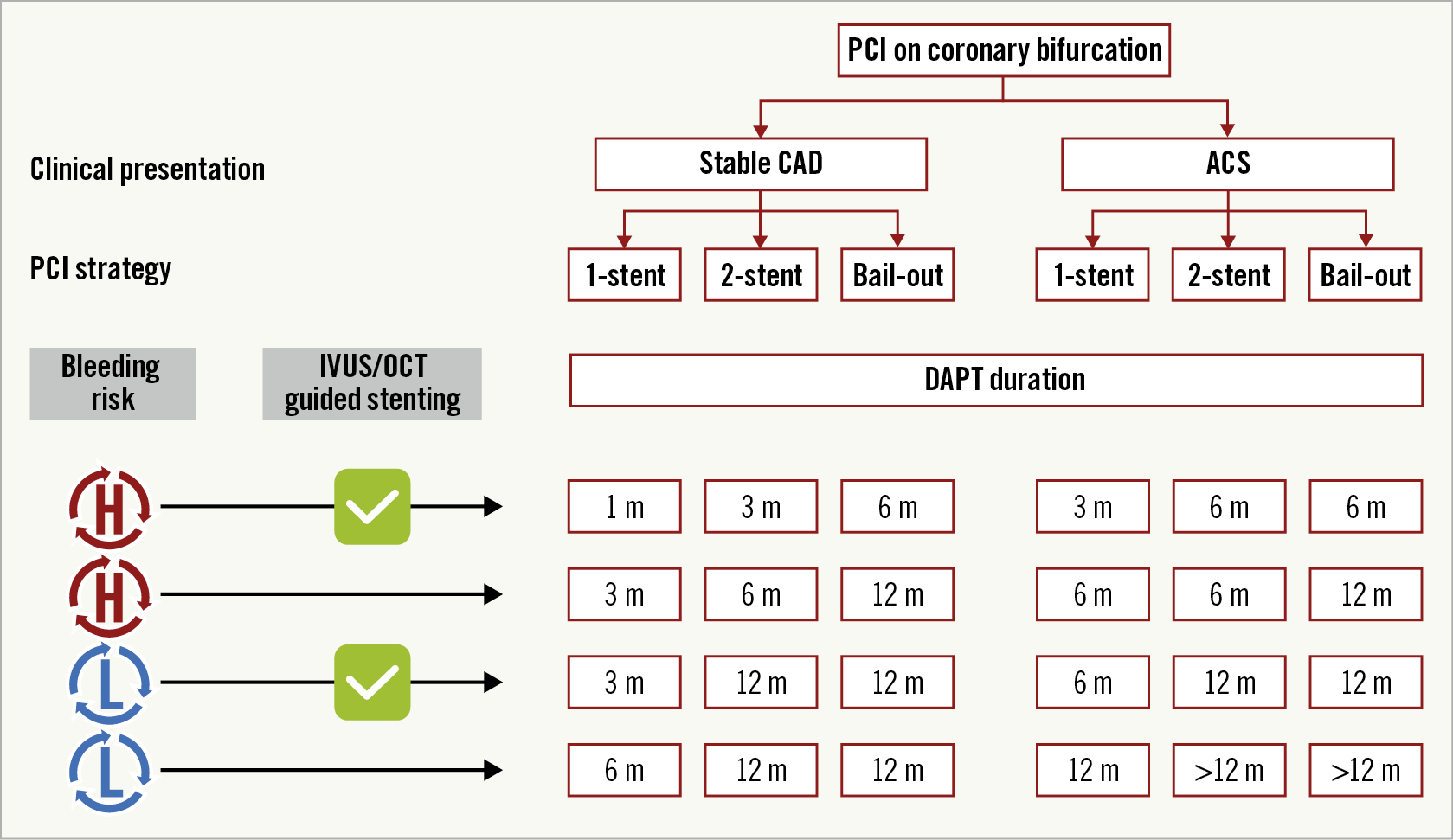

The selection and the duration of antithrombotic therapy after bifurcation PCI should take into account multiple factors. Although we acknowledge that much of the currently available evidence about antithrombotic therapy in bifurcation PCI is not derived from major dedicated studies, we here propose a decision-making algorithm for DAPT duration based primarily on the clinical presentation, the baseline bleeding risk, the stenting strategy, and the possible use of intracoronary imaging in patients not candidates to anticoagulant therapy (Central illustration).

Central illustration. Strategy algorithm proposal for DAPT duration after PCI of bifurcation in patients not candidates for oral anticoagulation. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CAD: coronary artery disease; DS: double stenting; IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; OCT: optical coherence tomography; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SS: single stenting

Strategy trials are keenly awaited to refine further the optimal antithrombotic regimen in patients undergoing bifurcation PCI.

Guest Editor

This paper was guest edited by Franz-Josef Neumann, MD; University Heart Centre Freiburg Bad Krozingen, Division of Cardiology and Angiology II, Bad Krozingen, Germany.

Conflict of interest statement

D.J. Angiolillo declares that he has received consulting fees or honoraria from Amgen, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Haemonetics, Janssen, Merck, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, and The Medicines Company and has received payments for participation in review activities from CeloNova and St. Jude Medical. D.J. Angiolillo also declares that his institution has received research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, CeloNova, CSL Behring, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Idorsia, Janssen, Matsutani Chemical Industry Co., Merck, Novartis, Osprey Medical, Renal Guard Solutions, and the Scott R. MacKenzie Foundation. G. Dangas declares that he has received consulting fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific and Biosensors, reports common stock (entirely divested) from Medtronic and declares that his institution has received institutional payments for research grants from AstraZeneca, Bayer and Daiichi Sankyo. D. Capodanno reports personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Bayer, Biosensors, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi Aventis, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. E. Barbato reports speaker’s fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific and GE. G. Renda reports speaker and consulting fees from Bayer, BMS-Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi Sankyo. R.F. Storey declares personal fees and institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, GlyCardial Diagnostics and Thromboserin, and personal fees from Amgen, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Haemonetics, Medscape, and Portola. M. Valgimigli reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Alvimedica/CID, Abbott Vascular, Daiichi Sankyo, Opsens, Bayer, CoreFlow, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Universität Basel | Dept. Klinische Forschung, Vifor, Bristol Myers Squibb SA, iVascular and Medscape, and grants and personal fees from Terumo. R. Mehran has received consulting fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medscape/WebMD, Siemens Medical Solutions, Philips/Volcano/Spectranetics, Roivant Sciences, Sanofi Italy, Bracco Group, Janssen, and AstraZeneca; has received grant support, paid to her institution, from Bayer, CSL Behring, DSI, Medtronic, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, OrbusNeich, Osprey Medical, PLC/RenalGuard, and Abbott Vascular; has received grant support and advisory board fees, paid to her institution, from Bristol-Myers Squibb; has received fees for serving on a data and safety monitoring board from Watermark Research Funding; has received advisory fees and lecture fees from Medintelligence (Janssen); and has received lecture fees from Bayer. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The Guest Editor reports lecture fees paid to his institution from Amgen, Bayer Healthcare, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Ferrer, Pfizer, and Novartis, consultancy fees paid to his institution from Boehringer Ingelheim, and grant support from Bayer Healthcare, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Edwards Lifesciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, and Pfizer.