Introduction

Permanent pacemaker (PPM) requirement is an important sequela after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) as it is associated with increased length of stay, increased cost of care and increased readmission rates1,2. There is conflicting evidence regarding the association between post-TAVI PPM requirement and mortality1,2,3,4. As the indications for TAVI expand to a younger, less comorbid cohort, the ramifications of having an additional device in situ long-term increase.

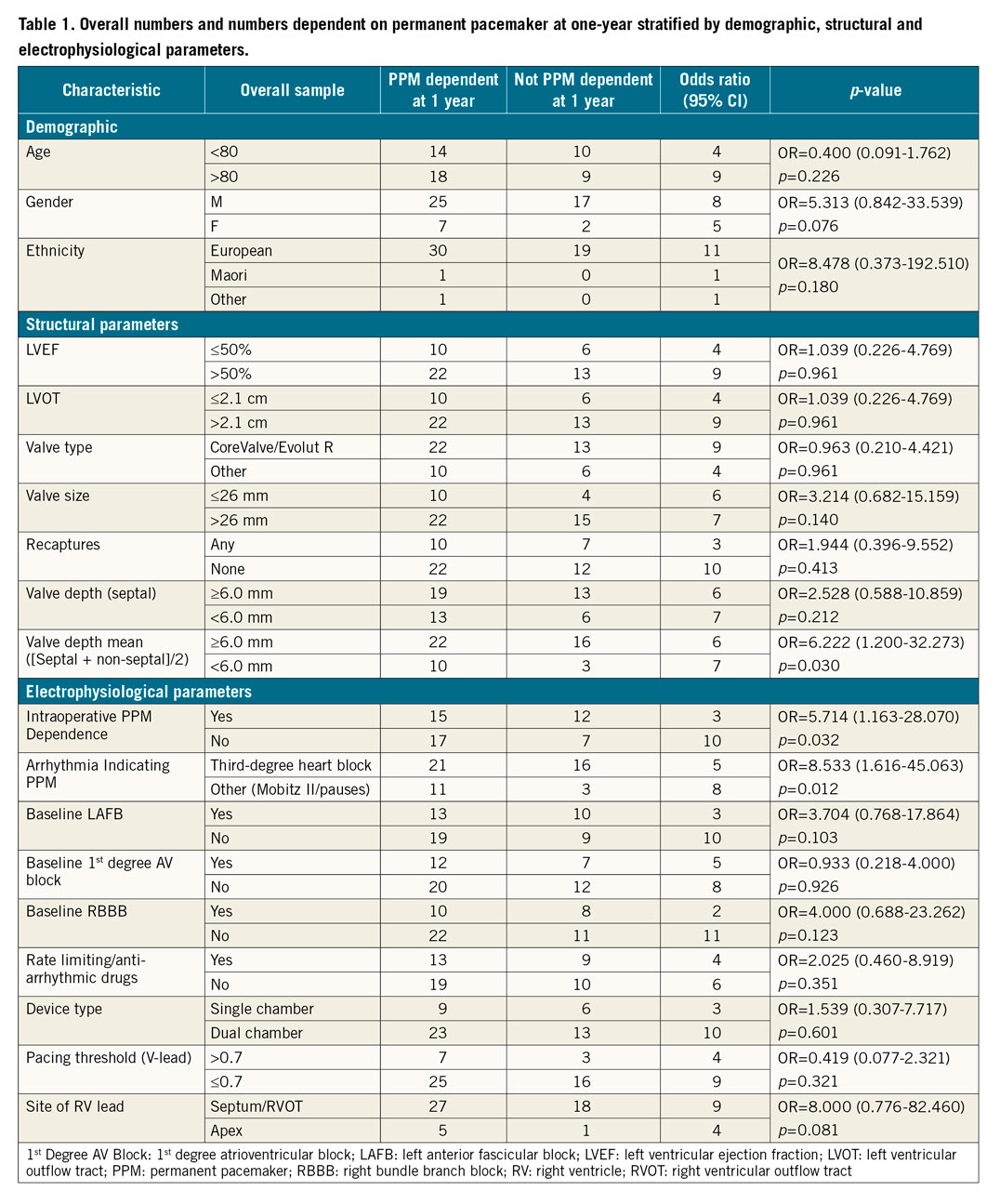

The aims of this retrospective analysis were to assess PPM dependence at one year and then to assess for any variables which may be predictive of PPM dependence at one year. We sought to assess PPM dependence at one year as a number of studies have suggested that up to half of those with PPMs inserted within 30 days post-TAVI are no longer dependent on their PPM at one year5,6. Moreover, gaining a better understanding of the determinants for dependence at one year may help delineate those whose conducting systems are possibly more likely to recover (and not be PPM dependent) and those whose conducting systems are less likely to recover (and be PPM dependent).

Methods

We used the All New Zealand Acute Coronary Syndrome Quality Improvement (ANZACS-QI) Device Database to identify all PPM insertions performed at Waikato Hospital in the 10-year interval between January 2009 and December 2018.

The ANZACS-QI Device Database is a web-based electronic database which captures a gamut of variables on each device implantation (PPM and implantable cardioverter defibrillators [ICDs]) performed in New Zealand’s public hospitals. The specifics regarding data flow and management and data outputs have been previously described7.

Of 1,373 patients who had PPM insertions at our institution in the pre-specified ten-year period, 33 had TAVI in the month prior to their PPM insertion. Of those, 32 received a PPM device interrogation at one year and were included in the final analyses. In the same time period, there were 344 TAVIs implanted at our institution.

PPM dependence was defined as having either (i) no escape rhythm when pacing rate lowered to 30 beats per minute, (ii) symptoms before pacing rate lowered to 30 beats per minute or (iii) a rhythm with a class I indication for pacing (for example, complete heart block or second-degree Mobitz II heart block).

Statistical analyses for odds ratios for predictors of PPM dependence were undertaken using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software).

Results

BASELINE DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

The demography in the analysed sample is in keeping with the known demographic profile of those with severe aortic stenosis in New Zealand whereby the incidence per 100,000 is markedly higher in the octogenarian group. This being said, although Ministry of Health data suggests a 2.5:1 incidence of aortic stenosis mortality between non-Maori and Maori, respectively, our cohort is disproportionately non-Maori (96.9%)8.

BASELINE STRUCTURAL-SPECIFIC PARAMETERS

From a structural perspective, 68.8% had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than 50% and over two thirds had a left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) diameter greater than 2.1 cm. CoreValve® (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and Evolut™ R (Medtronic) made up almost 70% (22/32) of the valves implanted. Other valves utilised included: Hydra (n=1, Vascular Innovations Co., Nonthaburi, Thailand), Jena (n=1, JenaValve Technology, Munich, Germany), Lotus™ (n=5, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA), SAPIEN XT (n=1, Edwards Lifesciences Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) and SAPIEN 3 (n=2, Edwards Lifesciences). A valve size of greater than 26 mm occurred in 68.8% (22/32) of the sample and recaptures (one or more) were required in 31.3% (10/32). Valve depth was noted at the septal side as well as a mean of the septal and non-septal sides; 68.8% (22/32) of the cohort had a mean valve implantation depth (defined as [septal side+non-septal side]/2) of at least 6 mm.

BASELINE ELECTROPHYSIOLOGICAL-SPECIFIC PARAMETERS

From an electrophysiological perspective, almost half were dependent on pacing during the procedure. Complete heart block made up 65.6% (21/32) of the indications for PPM insertion. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities captured preprocedurally included baseline left anterior fascicular block (40.6%), baseline first-degree heart block (37.5%) and baseline right bundle branch block (31.3%). A total of 40.6% (13/32) were on either AV nodal blocking or anti-arrhythmic medications prior to the procedure. Dual-chamber devices were sited in 71.9% (23/32) and 21.9% had ventricular pacing thresholds of greater than 0.7V. All but five out of 32 RV leads were sited either in the septum or right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT).

ONE-YEAR FOLLOW-UP OUTCOMES

Of those who had PPM insertions within a month after TAVI, 41% (13/32) were not PPM dependent at one year.

Of all the structural parameters, a mean valve implantation depth ([septal side+non-septal side]/2) of 6.0 mm or more had a statistically significant association with PPM dependence at one year (OR 6.222 [95% CI: 1.200-2.273]; p=0.030). Equally there was a trend towards PPM dependence with a valve size of greater than 26 mm, but this did not reach statistical significance (OR 3.214 [95% CI: 0.682-15.159]; p=0.140).

In terms of electrophysiological parameters, intraoperative PPM dependence (OR 5.714 [95% CI: 1.163-28.070]; p=0.032) and complete heart block as indication for PPM (OR 8.533 [95% CI: 1.616-45.063]; p=0.012) had statistically significant associations with PPM dependence at one year (Table 1).

Discussion

Our retrospective analysis of a ten-year period of PPM insertions post-TAVI has uncovered a number of valuable findings.

In terms of one-year follow-up outcomes, our rate of PPM dependence at one year of 59% echoes the rates observed in larger registry datasets, where up to 50% of those with a PPM inserted within one month after TAVI are no longer PPM dependent5,6. The consistency of this finding across registries would suggest that there may be an element of reversible, acute conduction system blockade which then improves gradually over time. This temporary insult may well be either ischaemic (in cases of coronary artery ostial occlusion) or mechanical9.

Indeed, the possibility of a predominantly mechanical mode of injury to the conducting system is supported by our finding of mean valve implantation depth being statistically significantly associated with PPM dependence at one year. Although implantation depth can be underestimated, as there is variability depending on the radiographic projection at the time of the aortogram, it provides a real-time, practical solution for the operators to guide discharge planning. Anatomically, the proximity of the left bundle branch of the His bundle to the right and non-coronary cusps makes the notion of a more deeply implanted valve causing impingement of the conducting system entirely plausible (either directly or by local myocardial oedema)10. Our finding is supported elsewhere in the literature – where not only valve implantation depth but also length of the membranous septum have been noted as predictors for high-degree AV block and need for PPM10,11,12. Specifically, there is also literature to support the use of mean valve implantation depth rather than depth at any specific coronary cusp as a potential predictor for PPM requirement13.

The analysis of our electrophysiological parameters highlighted the significance of the intraoperative PPM requirement and the presence of complete heart block as predictors of PPM dependence at one year. These findings may suggest that the presence of a higher degree blockade (manifested by requiring a PPM intraoperatively or developing CHB) rather than a more temporary AV node level lesion (for example, represented by a transient second-degree AV block) is a key driver for PPM dependence long term14. This being said, it remains difficult to ascertain whether a post-TAVI conduction disturbance will persist or self-resolve. In 2017, Tovia-Brodie et al attempted to find further predictors for PPM requirement with electrophysiology studies but were only able to garner similar findings to our study, whereby intraprocedural complete AV block and post-procedure high-grade AV block remained the only clear predictors. Use of electrophysiology studies (EPS) and, specifically, use of serial measurements of the His-Ventricular (HV) interval have yielded mixed results in terms of predicting the need for PPM in a number of small studies15,16,17.

Limitations

The limitations of our analysis include the limited sample size over the pre-specified ten-year period analysed as well as the definition and nature of PPM dependence. It is recognised that PPM dependence can be a variable phenomenon which fluctuates over time6. As such, a patient may well have significant conducting system disease which is not captured by our analysis as they do not appear to meet any of the criteria for dependence at the time of device interrogation. One could go on to speculate that the phenomenon of unexplained sudden deaths after TAVI may represent those with intermittent conducting system disease who are not recognised in the immediate post-operative phase. In addition, we recognise that using an endpoint of PPM dependence does not necessarily correlate to whether a PPM was appropriate for the same reasons noted above regarding the intermittent nature of PPM dependence. Indeed, the PPM which prevents our typically older and more comorbid TAVI patients from having a bradyarrhythmia-induced fall would be completely justified.

Future directions may include forms of electrophysiological testing beyond assessments of the HV interval, such as using rapid atrial pacing to detect Wenckebach physiology in the AV node, as this may serve as a predictor for PPM requirement as suggested by the work done by Krishnaswamy et al (2020)18. Equally, the use of implantable loop recorders after TAVI in selected higher-risk patients has shown promise in identifying those with post-TAVI late-onset conduction disturbances19. Furthermore, given the significant rates of those who do not appear to be PPM dependent at one year, consideration could be given to the use of pacing devices which could be implanted semi-permanently and then removed at a later point once it is clear that the conduction system has completely recovered.

In addition, as experience grows and valve technologies adapt, refinements in valve implantation depth as well recognition of key risk factors will continue to play a part in reducing rates of post-TAVI PPM requirement. Just as industry and clinicians have moved to reduce rates of paravalvular leak, the next frontier in improving TAVI outcomes will undoubtedly turn the focus onto post-procedural PPM requirement.

Conclusions

In keeping with other larger registry datasets, 41% of our cohort were not PPM dependent at one year. In this small retrospective analysis, mean valve implantation depth, PPM dependence during TAVI and complete heart block as indication for PPM insertion were predictors of PPM dependence at one year – all those PPM-dependent at one year in this cohort had at least one of these predictors. Larger studies with collaboration between structural and electrophysiology subspecialties are required to glean further insights into and improve rates of post-TAVI PPM requirement and dependence in order to continue to allow TAVI to evolve as a safe and reproducible intervention for aortic stenosis.

Impact on daily practiceThe findings from this 10-year, single-centre, retrospective analysis will help clinicians identify patients who are not only at highest risk for requiring post-TAVI pacemaker insertion but also those who are most likely to be dependent in the long term on their pacemaker. Ultimately, this can help TAVI operators risk stratify patients based on measurable structural and electrophysiological parameters. |

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.