Introduction

Patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS) are exposed to a high risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalisation for heart failure if not treated with a valve replacement1. Progressive ageing in Western countries has led to an increasing number of patients with severe degenerative AS, along with comorbidities, at high or prohibitive risk for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). In these settings, balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) has previously been performed, but its relevant rate of complications, along with its potentially life-threatening2 and poor long-term results, has progressively limited its indications. The advent of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has led to a renewal of interest in BAV in recent years. Today, the procedure can be recommended not only as a destination therapy for patients excluded from TAVR but as a bridge to TAVR (or to SAVR) or as a stratification tool for certain high-risk patients who are not immediate candidates for TAVR3. In addition, recent data suggest that technical improvements in the BAV technique have reduced the procedural risks. Thus, today, if a minimally invasive approach is used, BAV can be performed with greater safety4 by trained operators in centres without onsite cardiac surgery5.

We aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BAV performed by trained operators in a high-volume centre (BAV referral centre) without onsite cardiac surgery. In addition, the effects of the progressive implementation of a minimalistic approach (radial access, ultrasound-guided vascular puncture, left ventricular pacing through a stiff guidewire) on periprocedural complications are evaluated.

Methods

PATIENT POPULATION

Data on consecutive patients with severe symptomatic AS (aortic valve area [AVA] <1 cm2) undergoing BAV at the high-volume Ospedale Maggiore Cath Lab from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2021 were prospectively collected in a dedicated database. Patients were retrospectively subdivided into 4 cohorts according to their indications for BAV: 1) bridge to TAVR (B-TAVR); 2) bridge to SAVR (B-SAVR); 3) cardiogenic shock; and 4) palliation of symptoms in patients unsuitable for TAVR or SAVR (palliation).

The B-SAVR and the B-TAVR groups included patients initially deemed ineligible for SAVR or TAVR because of their critical condition (acute pulmonary oedema, heart failure or syncope) or who were highly symptomatic (New York Heart Association [NYHA] Class III) during the wait for TAVR or SAVR. According to the echocardiographic evaluation, patients were divided into 3 categories: high-gradient AS (mean gradient ≥40 mmHg, peak velocity ≥4.0 m/s, aortic valve area [AVA] ≤1 cm2), low-gradient AS with reduced ejection fraction (mean gradient <40 mmHg, AVA ≤1 cm2, left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] <50%), and low-gradient AS with preserved ejection fraction (mean gradient <40 mmHg, AVA ≤1 cm2, LVEF ≥50%).

BAV PROCEDURE

All procedures were performed with the Cristal Balloon (Balt), mainly in its 20 mm diameter version; the size of the balloon length was determined using the echocardiographic measurement of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT). Both femoral and radial access were used. For transradial aortic valvuloplasty (TRAV), the introducer was 8 Fr, 11 cm input sheath (Medtronic), and the balloon length was 110 cm, 20 ml, compatible with the 8 Fr. In the other cases, the standard retrograde technique via the right or left femoral artery was used, with ultrasound (US)-guided femoral puncture in most cases. In these cases, an 8 to 10 Fr introducer was used.

A low-dose heparin bolus was administered after sheath insertion in all patients (40-50 IU/kg).

Rapid ventricular pacing for pulse abrogation was achieved using a 0.035-inch left ventricular support wire and, only in a few cases until 2019, using a transvenous temporary pacemaker (TTP). Balloon inflation was started as soon as pulse abrogation was observed during rapid pacing (180-200 beats/min). Thus, the balloon diameter was modulated with manual inflation in order to achieve a 1:1 balloon-to-annulus ratio, confirmed by the complete sealing of the valvular orifice and aortic pulse abrogation. In 8 cases, a 23 mm balloon was used to achieve this 1:1 balloon-to-annulus ratio. Access site closure was performed either with manual compression or with a percutaneous approach (Perclose ProGlide; Abbott).

DEFINITION AND OUTCOMES

The logistic European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation score (EuroSCORE II) was calculated for all patients. Peripheral artery disease included a history of claudication, previous vascular surgery, or documented peripheral arterial stenosis >50%. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as a glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min calculated by the Cockcroft-Gault formula. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was identified by long-term use of bronchodilators, steroids, or oxygen. High bleeding risk was identified in patients with a haemoglobin value <11 g/dl, according to the Academic Research Consortium (ARC)6. Cardiogenic shock was characterised by systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg with signs of low peripheral perfusion or the necessity to administer inotropes for circulatory support. The occurrence of the following in-hospital events was recorded: death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, vascular complications, bleedings, acute kidney injury (AKI), acute heart failure, and severe acute aortic regurgitation. The Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC)-2 document was used to standardise endpoint definitions7. Severe acute aortic regurgitation (AR) was defined as a swift and steep drop of aortic diastolic pressure, along with the rapid equilibration of left ventricular (LV) and aortic pressures, which was not present at baseline and is associated with rapid circulatory collapse.

The efficacy endpoint was a reduction in the mean invasive gradient of >30%. In-hospital and periprocedural death and complications after BAV were the safety endpoint. Follow-up was complete for all patients and used different sources: hospital files, outpatient clinics, hospital discharge records, and civil death records.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are expressed as mean (±standard deviation [SD]) and comparisons between groups were performed with the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test when suitable. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Cumulative event rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazard regression method (and logistic regression analyses at 30 days and 1 year) was used to examine the association of clinical, echocardiographic, and procedural variables with mortality during follow-up. Multivariate analyses, including all variables with p≤0.10 at univariate analysis, were performed to identify independent predictors of mortality at 30 days and 1 year. All analyses were carried out using the SPSS statistical software package version 24.0 (IBM). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

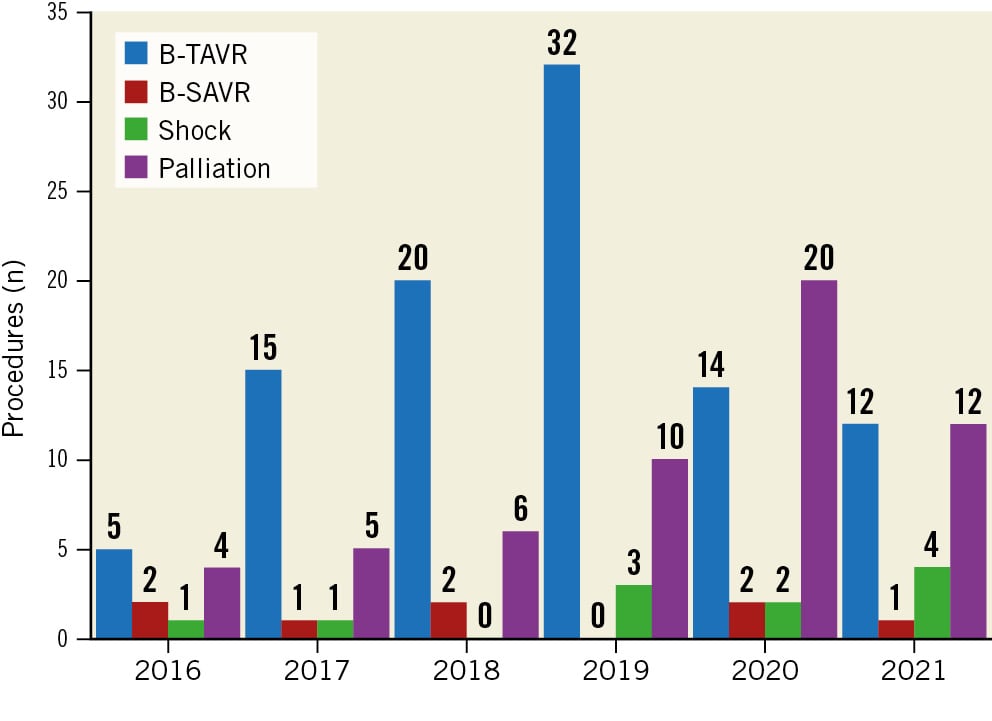

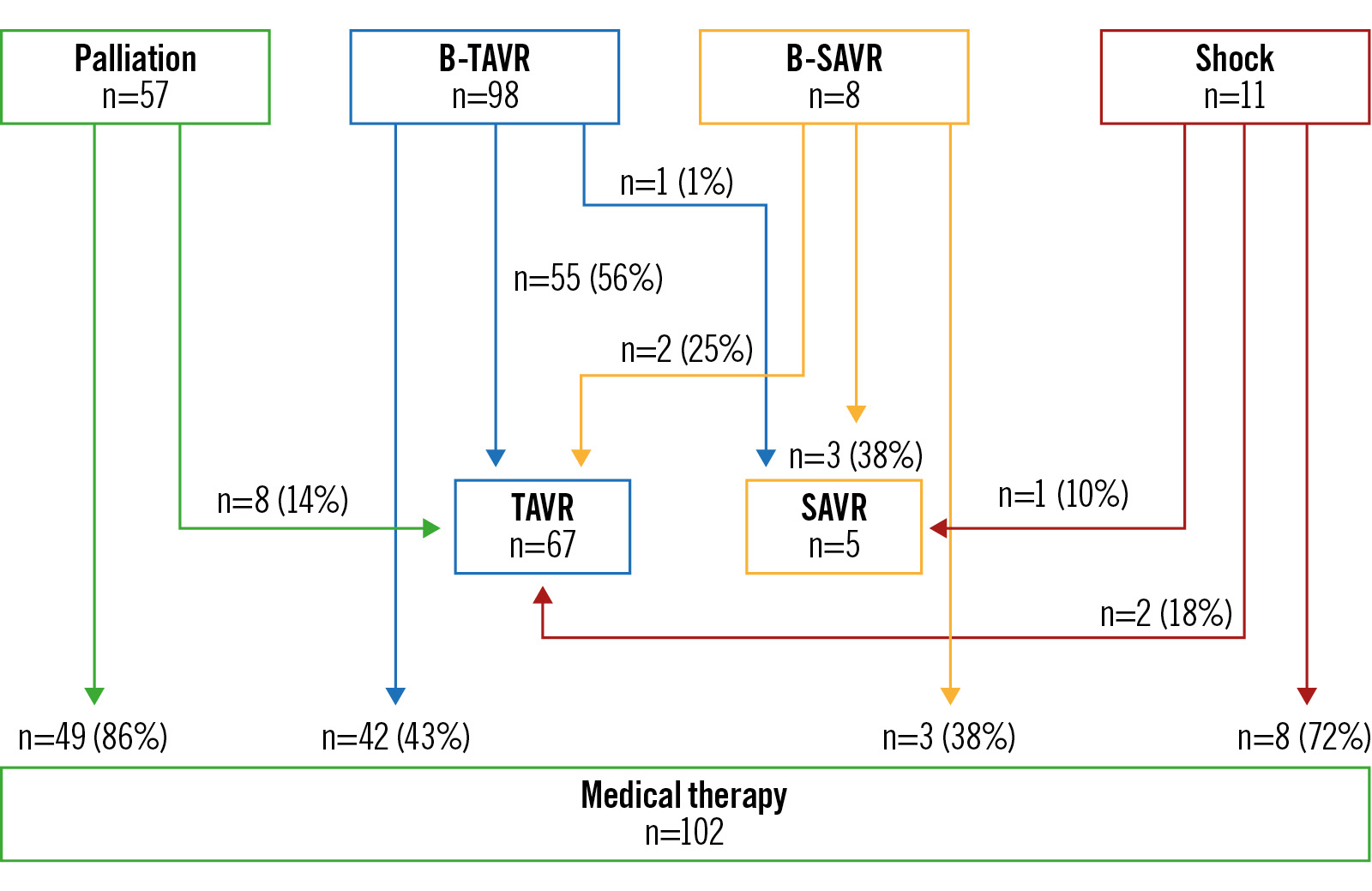

From January 2016 to December 2021, 174 patients underwent BAV at our centre. Twelve patients underwent a repeat procedure, with one patient receiving it three times; thus, the total number of procedures was 187 (Figure 1). Patients were 85.0±5.4 years old and had a high risk score (EuroSCORE II 10.1±9.9) (Table 1). Ten patients had previously undergone BAV. Typical clinical presentations were heart failure (n=124; 71%) or syncope (n=42; 24%).

According to the indications, we identified 4 cohorts: 1) bridge to TAVR (n=98; 56%); 2) cardiogenic shock (n=11; 6%); 3) bridge to SAVR (n=8; 5%); and 4) palliation (n=57; 33%). Most patients had high-gradient aortic stenosis (mean gradient ≥40 mmHg, peak velocity ≥4.0 m/s, AVA ≤1 cm2 or ≤0.6 cm2/m2) (Table 2)8.

Femoral access was standard (Table 3), with US-guided puncture of the femoral artery itself implemented in 2019. In a patient with significant peripheral chronic obliterative arteriopathy and with no other access, a US-guided brachial puncture was performed.

In order to reduce vascular complications in cases with an additional access site, rapid ventricular pacing for pulse abrogation was performed using a 0.035-inch left ventricular support wire. A few cases had a transvenous temporary pacemaker (TTP) in place (until 2019), mostly with right bundle branch block on a standard electrocardiogram (ECG).

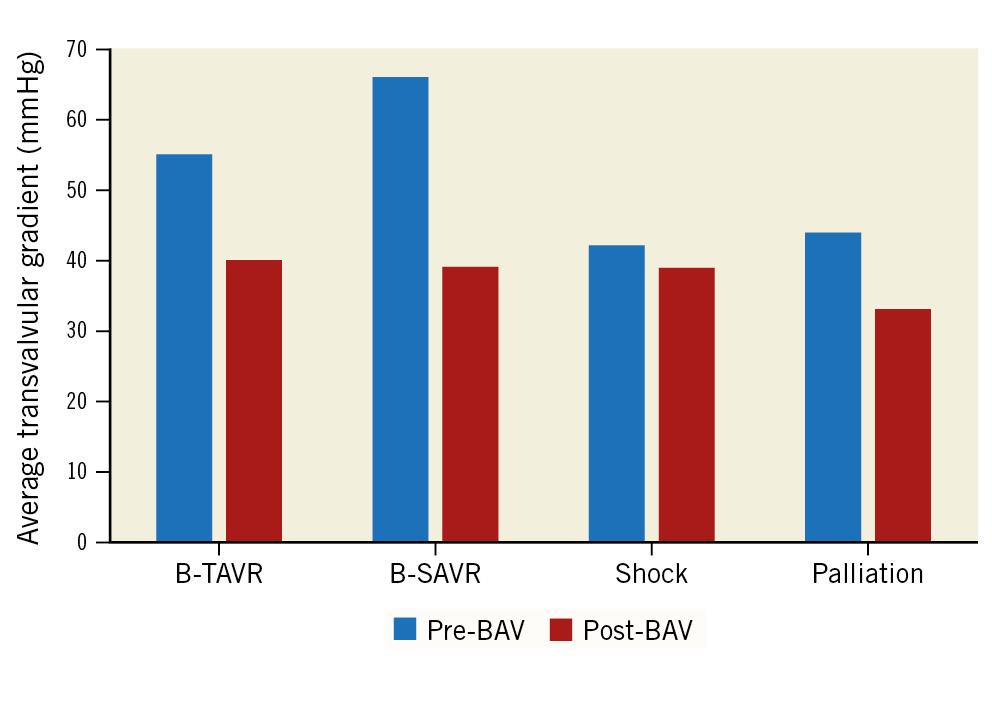

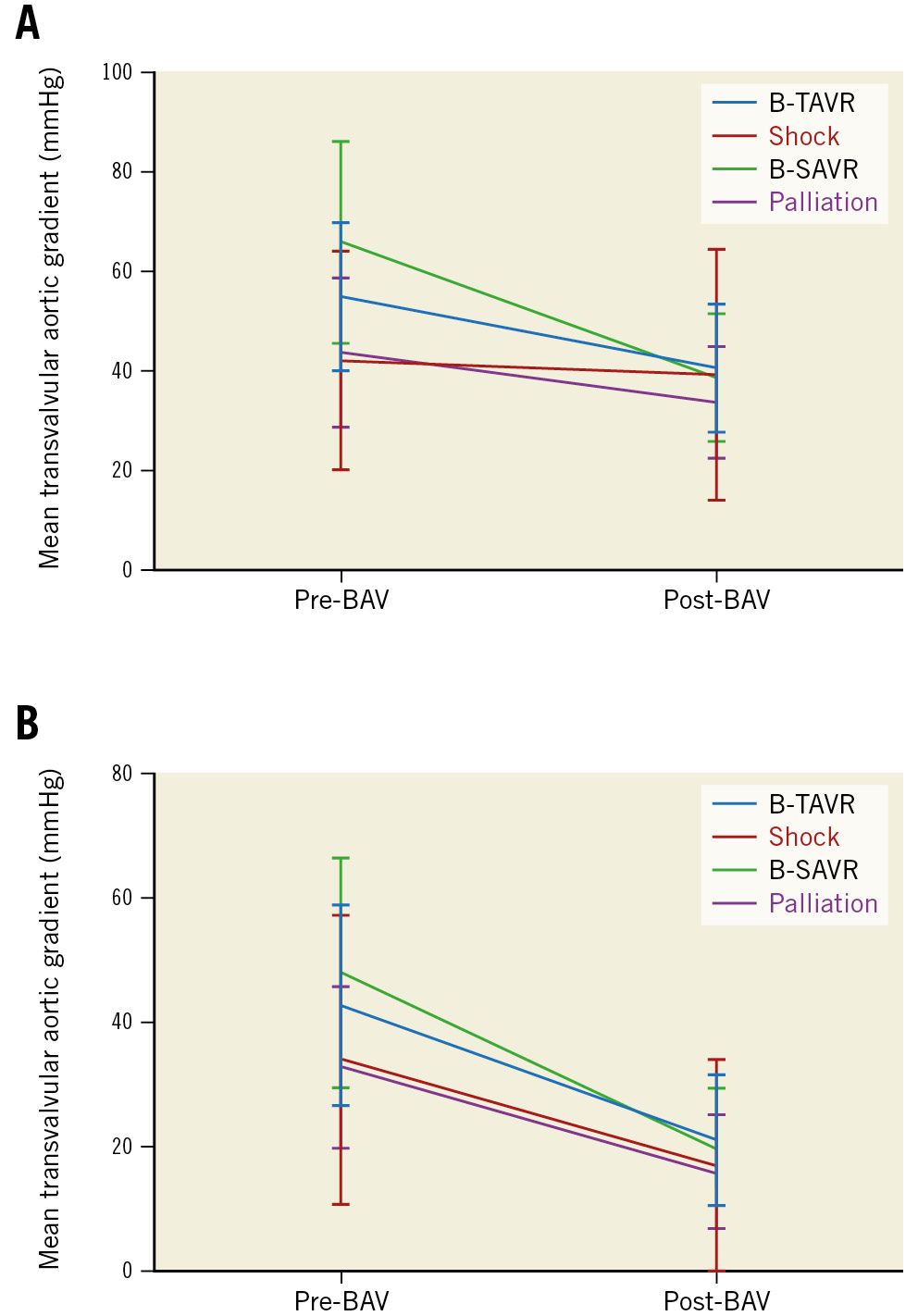

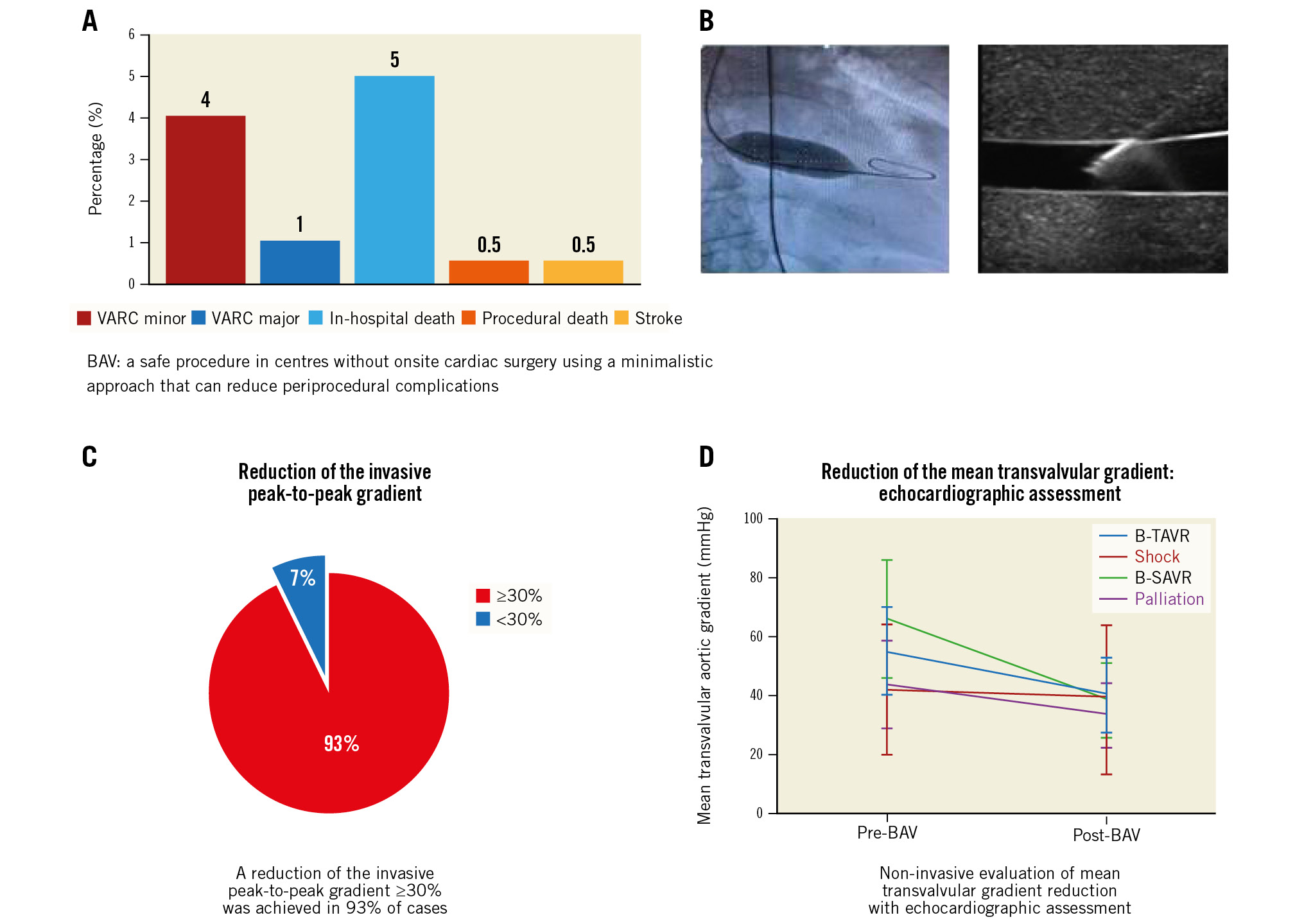

The efficacy endpoint, a reduction of the invasive peak-to-peak gradient ≥30%, was achieved in 93% of cases (Figure 2, Figure 3A, Figure 3B, Central illustration). Invasive maximum and mean gradients were reduced from 56±24 mmHg and 39±17 mmHg to 28±15 mmHg and 20±12 mmHg, respectively. A statistically significant improvement from baseline was noted in the invasive peak-to-peak gradient in all groups (p=0.007) (Table 3). In-hospital mortality was 5% and occurred predominantly in patients with cardiogenic shock that had received an emergent, rescue BAV (Table 4). There was only one periprocedural death, which was probably due to aortic annulus rupture. Vascular complications occurred primarily before 2019. After this date, the routine use of US-guided puncture reduced vascular complication rates.

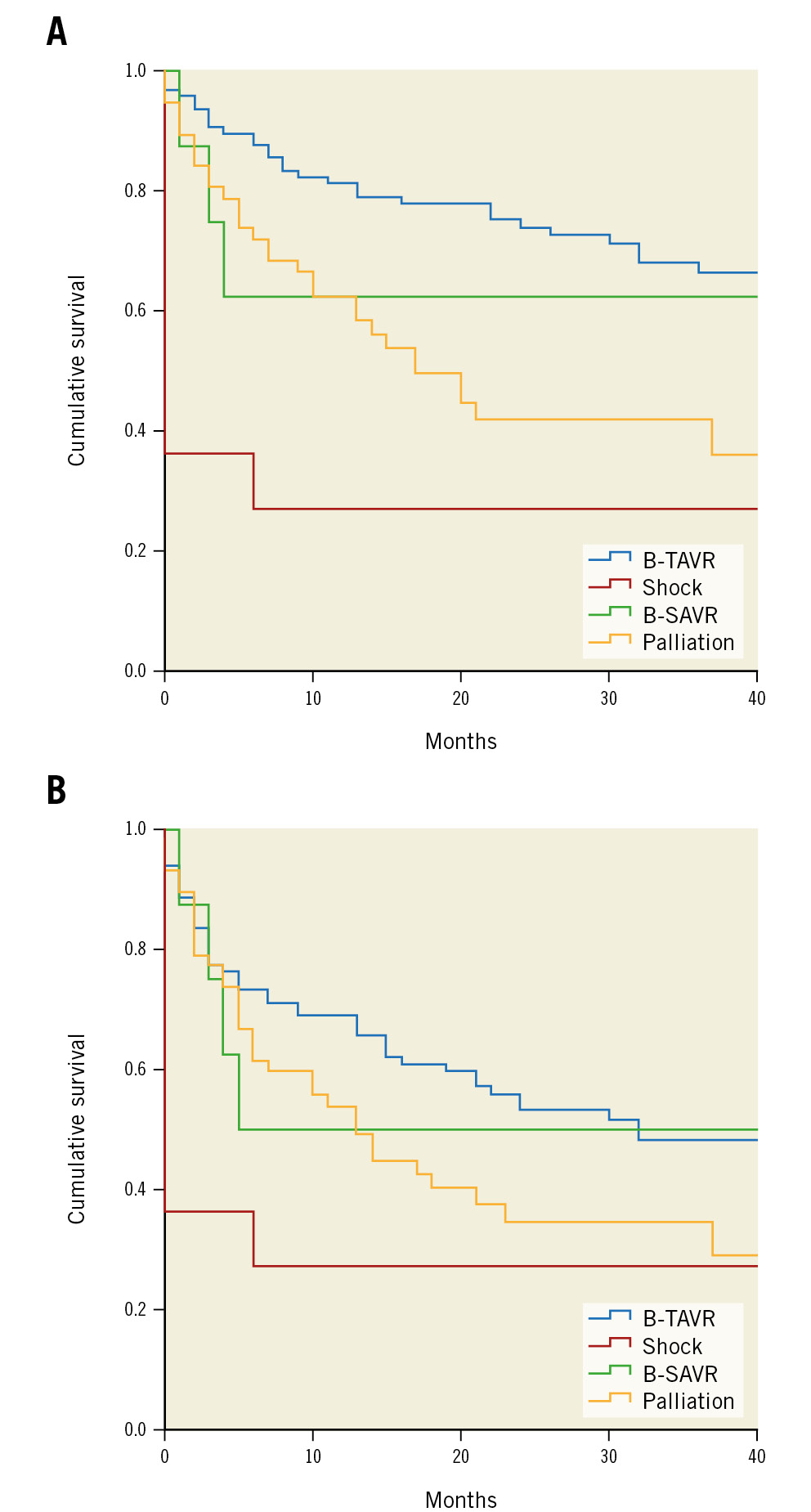

Clinical outcomes are listed in Table 5. One-year mortality was 28.7%: the highest mortality was in the shock group (73%) and the lowest in the B-TAVR group (18%). The incidence of 1-year death or hospitalisation for heart failure (HF) was lower in the B-TAVR group. Cumulative rates of clinical outcomes at 40-month follow-up are shown in Figure 4A and Figure 4B. Variables associated with mortality during BAV follow-up are listed in Table 6.

Safety was confirmed, even in repeat procedures. Repeat BAV was not associated with a higher risk of death (odds ratio [OR] 1.176, 95% CI: 0.364-3.800; p=0.787) or vascular complications (no repeat procedure had any vascular complication).

Figure 1. Number of balloon aortic valvuloplasty procedures per year according to indication. B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Table 1. Demographics and baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | All patients (n=174) | B-TAVR (n=98) | B-SAVR (n=8) | Shock (n=11) | Palliation (n=57) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 85.0±5.4 | 85.0±4.4 | 74.9±7.7 | 83.3±5.6 | 86.9±5.0 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 45.4 (79) | 50.0 (49) | 25.0 (2) | 45.5 (5) | 40.4 (23) | 0.456 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.2±4.3 | 25.8±4.0 | 28.3±4.8 | 27.0±6.0 | 26.5±4.5 | 0.316 |

| Diabetes | 25.3 (44) | 19.4 (19) | 37.5 (3) | 45.5 (5) | 29.8 (17) | 0.068 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 51.1 (89) | 51.0 (50) | 75.0 (6) | 63.6 (7) | 45.6 (26) | 0.347 |

| Hypertension | 82.2 (143) | 83.7 (82) | 75.0 (6) | 72.7 (8) | 82.5 (47) | 0.823 |

| Cancer | 26.4 (46) | 27.6 (27) | 25.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 29.8 (17) | 0.218 |

| COPD | 23.0 (40) | 20.4 (20) | 12.5 (1) | 36.4 (4) | 26.3 (15) | 0.412 |

| Peripheral arteriopathy | 46.0 (80) | 49 (48) | 25.0 (2) | 45.5 (5) | 43.9 (25) | 0.637 |

| Neurological dysfunction | 15.5 (27) | 15.3 (15) | 0.0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 19.3 (11) | 0.634 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 37.9 (66) | 34.7 (34) | 0.0 (0) | 45.5 (5) | 47.4 (27) | 0.028 |

| Pacemaker | 7.5 (13) | 6.1 (6) | 0.0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 10.5 (6) | 0.523 |

| Prior MI | 23 (40) | 18.4 (18) | 25.0 (2) | 36.4 (4) | 28.1 (16) | 0.237 |

| Prior revascularisation PCI or CABG | 19.5 (34) | 18.4 (18) | 12.5 (1) | 36.4 (4) | 19.3 (11) | 0.539 |

| Prior CVA | 11.5 (20) | 13.3 (13) | 0.0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 10.5 (6) | 0.909 |

| Prior BAV | 5.2 (9) | 5.1 (5) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 7.0 (4) | 0.901 |

| Anaemia/Hb ≤11 g/dl | 29.9 (52) | 23.5 (23) | 25.0 (2) | 36.4 (4) | 40.4 (23) | 0.145 |

| CKD (GFR <60ml/min) | 59.2 (103) | 46.9 (46) | 0.0 (0) | 100 (11) | 80.7 (46) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis | 1.1 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.8 (1) | 0.998 |

| EF ≤35% | 19.0 (33) | 12.2 (12) | 12.5 (1) | 36.4 (4) | 28.1 (16) | 0.029 |

| Stable angina | 8.6 (15) | 10.2 (10) | 0.0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 7.0 (4) | 0.957 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 14.9 (26) | 13.3 (13) | 12.5 (1) | 27.3 (3) | 15.8 (9) | 0.588 |

| NYHA III-IV | 71.3 (124) | 67.3 (66) | 75.0 (6) | 72.7 (8) | 77.2 (44) | 0.629 |

| Syncope | 24.1 (42) | 23.5 (23) | 37.5 (3) | 18.2 (2) | 24.6 (14) | 0.804 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 5.7 (10) | 1.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 72.7 (8) | 1.8 (1) | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II, % | 10.1±9.9 | 7.7±6.1 | 2.5±1.7 | 26.3±20.3 | 12.5±10.0 | <0.001 |

| Porcelain aorta | 2.3 (4) | 3.1 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.8 (1) | 0.998 |

| Data are shown as mean±SD for continuous variables and % (absolute numbers) for dichotomous variables. *for comparison between subgroups. BAV: balloon aortic valvuloplasty; BMI: body mass index; B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; EF: ejection fraction; EuroSCORE: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; Hb: haemoglobin; MI: myocardial infarction; NYHA: New York Heart Association Functional Class; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

Table 2. Echocardiographic parameters before and after balloon aortic valvuloplasty.

| Pre-BAV (n=174) |

All patients (n=174) | B-TAVR (n=98) |

B-SAVR (n=8) |

Shock (n=11) |

Palliation (n=57) |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVA, cm2 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.6±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.101 |

| Average transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 51.1±16.7 | 54.9±14.9 | 65.7±20.2 | 42.0±22.0 | 43.6±14.9 | <0.001 |

| Peak-to-peak transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 81.1±25.9 | 86.6±24.8 | 92.2±31.4 | 64.7±33.0 | 72.4±22.5 | 0.001 |

| Aortic regurgitation | ||||||

| Moderate/severe | 0.6 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.8 (1) | 0.446 |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Mitral valve regurgitation | ||||||

| Moderate/severe | 10.9 (19) | 9.2 (9) | 12.5 (1) | 9.1 (1) | 14.0 (8) | 0.833 |

| Severe | 3.4 (6) | 2.0 (2) | 0 (0) | 18.2 (2) | 3.5 (2) | 0.107 |

| LVEF, % | 49.4±13.9 | 53.1±12.6 | 51.7±18.7 | 35.6±12.5 | 45.4±12.9 | <0.001 |

| Post-BAV (n=126) | ||||||

| AVA, cm2 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.9±0.1 | 0.5±0.1 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.010 |

| Average transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 38.3±13.5 | 40.5±12.9 | 38.6±12.8 | 39.1±25.1 | 33.7±11.2 | 0.096 |

| Peak-to-peak transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 62.9±21.1 | 67.3±20.3 | 55.0±19.0 | 57.5±39.6 | 56.7±17.7 | 0.049 |

| Aortic regurgitation | ||||||

| Moderate/severe | 0.6 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.8 (1) | 0.427 |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Mitral valve regurgitation | ||||||

| Moderate/severe | 5.2 (9) | 2.0 (2) | 0 (0) | 18.2 (2) | 8.8 (5) | 0.027 |

| Severe | 1.7 (3) | 1.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 1.8 (1) | 0.304 |

| LVEF, % | 48.3±13.7 | 51.6±12.9 | 36.7±15.1 | 29.2±5.7 | 45.7±13.0 | 0.002 |

| Data are shown as mean±SD for continuous variables and % (absolute numbers) for dichotomous variables. *for comparison between subgroups. AVA: aortic valve area; BAV: balloon aortic valvuloplasty; B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

Table 3. Procedural and haemodynamic data.

| All patients (n=174) | B-TAVR (n=98) | B-SAVR (n=8) | Shock (n=11) | Palliation (n=57) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balloon size, mm | 19.5±1.2 | 19.4±1.2 | 20.5±1.7 | 19.1±1.0 | 19.5±1.3 | 0.069 |

| Peak-to-peak gradient pre-BAV, mmHg | 55.9±23.9 | 60.4±24.1 | 67.1±22.6 | 52.1±33.3 | 46.9±18.6 | 0.003 |

| Peak-to-peak gradient post-BAV, mmHg | 27.7±14.5 | 30.1±14.8 | 30.6±13.1 | 24.3±20.2 | 23.8±11.7 | 0.060 |

| Average gradient pre-BAV, mmHg | 39.3±16.7 | 42.5±16.7 | 48.1±18.5 | 34.3±23.3 | 33.0±13.1 | 0.004 |

| Average gradient post-BAV, mmHg | 19.8±11.7 | 21.2±10.7 | 20.1±9.5 | 17.2±17.1 | 16.2±9.2 | 0.043 |

| TTP | 13.8 (24) | 17.3 (17) | 25.0 (2) | 9.1 (1) | 7.0 (4) | 0.168 |

| LV guidewire pacing | 60.3 (105) | 66.3 (65) | 50.0 (4) | 9.1 (1) | 61.4 (35) | 0.002 |

| US-guided femoral puncture | 72 (118) | 65.3 (64) | 50.0 (4) | 72.7 (8) | 73.7 (42) | 0.486 |

| Radial approach | 5.2 (9) | 6.1 (6) | 0.0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 3.5 (2) | 0.689 |

| PCI | 14.4 (25) | 19.4 (19) | 25.0 (2) | 9.1 (1) | 5.3 (3) | 0.047 |

| Improvement from baseline peak-to-peak gradient | 28.5±13.6 | 30.6±13.8 | 36.5±16.7 | 27.8±16.1 | 23.6±10.6 | 0.007 |

| Data are shown as mean±SD for continuous variables and % (absolute numbers) for dichotomous variables. *for comparison between subgroups. BAV: balloon aortic valvuloplasty; B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement; LV: left ventricular; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: standard deviation; TTP: transvenous temporary pacemaker; US: ultrasound | ||||||

Figure 2. Average transvalvular gradient: echocardiographic assessment. BAV: balloon aortic valvuloplasty; B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Figure 3. Reduction of mean transvalvular gradient after BAV. A) Reduction of mean transvalvular gradient (mean value and standard deviation) after BAV; echocardiographic assessment. B) Reduction of mean transvalvular gradient (mean value and standard deviation) after BAV; invasive gradient. BAV: balloon aortic valvuloplasty; B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Central illustration. Efficacy and safety of a minimalistic balloon aortic valvuloplasty strategy in centres without heart surgery. A) Periprocedural complications. B) Balloon inflation in aortic valvuloplasty, left panel and ultrasound-guided vascular puncture, right panel. C) Reduction of the invasive peak-to-peak gradient. D) Non-invasive evaluation of mean transvalvular gradient reduction.BAV: ballon aortic valvuloplasty; B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement; VARC: Valve Academic Research Consortium

Table 4. In-hospital outcomes.

| All patients (n=174) | B-TAVR (n=98) | B-SAVR (n=8) | Shock (n=11) | Palliation (n=57) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital death | 5.2 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 63.6 (7) | 3.5 (2) | <0.001 |

| Periprocedural death | 0.6 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.8 (1) | 0.998 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.1 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.199 |

| Stroke | 0.6 (1) | 1.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.998 |

| Major vascular complications¶ | 1.1 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.8 (1) | 0.938 |

| Minor vascular complications¶ | 5.2 (9) | 6.1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.3 (3) | 0.998 |

| Life-threatening/disabling bleeding¶ | 0.6 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.8 (1) | 0.430 |

| Major bleeding¶ | 2.9 (5) | 2.0 (2) | 0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 3.5 (2) | 0.448 |

| Minor bleeding¶ | 5.2 (9) | 6.1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.3 (3) | 0.999 |

| Acute kidney injury¶ | 3.4 (6) | 1.0 (1) | 0 (0) | 27.3 (3) | 3.5 (2) | 0.004 |

| Data are shown as % (absolute numbers). *for comparison between subgroups. ¶according to Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 classification. B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement | ||||||

Table 5. Cumulative clinical outcomes during follow-up.

| All patients (n=174) | B-TAVR (n=98) | B-SAVR (n=8) | Shock (n=11) | Palliation (n=57) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat BAV at 1 year | 4.6 (8) | 5.1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.3 (3) | 0.998 |

| Death at 30 days | 7.5 (13) | 3.1 (3) | 0 (0) | 63.6 (7) | 5.3 (3) | <0.001 |

| Death at 1 year | 28.7 (50) | 18.4 (18) | 37.5 (3) | 72.7 (8) | 36.8 (21) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalisation for HF at 1 year | 21.2 (36) | 21.9 (21) | 25.0 (2) | 0 (0) | 23.2 (13) | 0.390 |

| Death or hospitalisation for HF at 1 year | 39.3 (68) | 30.9 (30) | 50.0 (4) | 72.7 (8) | 45.6 (26) | 0.023 |

| Data are shown as % (absolute numbers). *for comparison between subgroups. BAV: balloon aortic valvuloplasty; B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement; HF: heart failure | ||||||

Figure 4. Clinical outcomes after BAV. A) Clinical outcomes after BAV for different indications. B) Clinical outcomes: cumulative survival or freedom from rehospitalisation for heart failure. B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Table 6. Predictors of mortality during follow-up after standalone BAV.

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| 30 days | ||||

| Univariate analysis | ||||

| Diabetes | 6.296 | 1.895 | 20.915 | 0.003 |

| CKD | 4.965 | 1.088 | 22.663 | 0.039 |

| Shock | 21.780 | 7.203 | 65.860 | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.111 | 1.071 | 1.151 | <0.001 |

| Average gradient pre-BAV <40 mmHg | 6.505 | 1.904 | 22.232 | 0.003 |

| Mitral valve regurgitation >3+ | 3.575 | 1.169 | 10.933 | 0.025 |

| LVEF ≤35% | 5.463 | 1.835 | 16.263 | 0.002 |

| Guidewire pacing | 0.187 | 0.052 | 0.681 | 0.011 |

| Multivariate Cox analysis | ||||

| Diabetes | 7.269 | 1.222 | 43.244 | 0.029 |

| CKD | 68.789 | 3.407 | 1,388.693 | 0.006 |

| Shock | 13.842 | 1.746 | 109.747 | 0.013 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.117 | 1.054 | 1.184 | <0.001 |

| Guidewire pacing | 0.122 | 0.021 | 0.706 | 0.019 |

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| 1 year | ||||

| Univariate analysis | ||||

| Shock | 5.417 | 2.426 | 12.095 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 2.923 | 1.663 | 5.136 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.838 | 1.050 | 3.220 | 0.033 |

| Previous MI | 2.509 | 1.411 | 4.460 | 0.002 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.070 | 1.045 | 1.0895 | <0.001 |

| CKD | 1.783 | 0.994 | 3.198 | 0.053 |

| Average gradient pre-BAV <40 mmHg | 2.977 | 1.653 | 5.361 | <0.001 |

| Mitral valve regurgitation >3+ | 2.008 | 1.049 | 3.845 | 0.035 |

| LVEF ≤35% | 2.838 | 1.579 | 5.101 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate Cox analysis | ||||

| EuroSCORE II | 1.043 | 1.010 | 1.076 | 0.010 |

| Diabetes | 2.670 | 1.432 | 4.978 | 0.002 |

| Previous MI | 2.894 | 1.513 | 5.539 | 0.001 |

| LVEF ≤35% | 1.843 | 0.958 | 3.547 | 0.067 |

| Mitral valve regurgitation >3+ | 2.085 | 1.006 | 4.323 | 0.048 |

| BAV: balloon aortic valvuloplasty; CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; EuroSCORE: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; HR: hazard ratio; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MI: myocardial infarction | ||||

Discussion

The main findings of our study are as follows:

1. BAV can be safely performed in centres without onsite heart surgery, with few procedural complications and low in-hospital mortality. Even repeat procedures are safe.

2. One-year mortality is higher for patients with BAV as palliation or with shock at presentation.

3. The risk of rehospitalisation is higher in patients who do not proceed to aortic valve replacement.

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty was first proposed in 1986 by Cribier as an alternative to SAVR in patients with severe senile aortic stenosis. Subsequent studies confirmed the utility of standalone BAV in improving symptoms but showed no effect on survival9. In addition, the BAV procedure was associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Therefore, after an initial peak in the 1990s, the utilisation of BAV decreased dramatically, being reserved for palliative indications. The introduction of TAVR has renewed interest in BAV, mainly due to the increased referral of elderly patients with multiple risk factors who were previously untreated. Remarkably, a significant proportion of patients remain without any option of definitive treatment. For most of these remaining no-option patients, BAV can offer significant immediate haemodynamic and clinical improvement with an improved quality of life. It is a low-cost and relatively safe procedure in experienced hands. It can be performed by trained operators in centres without onsite cardiac surgery using a minimalistic approach (radial access or ultrasound-guided vascular puncture, left ventricular pacing through a stiff guidewire) that can reduce periprocedural complications. In our cohort, the rates of periprocedural adverse events were lower compared to earlier registries2 and comparable to that of centres with onsite surgery10. Additionally, there were no cases of acute severe aortic regurgitation. If this occurs, manipulating a pigtail catheter reinforced with a stiff guidewire can remobilise the blocked cusp, often a cause of AR11. In case of any life-threatening developments, our team was equipped and trained to perform lifesaving manoeuvres (e.g., pericardiocentesis, blood transfusion, advanced cardiovascular life support [ACLS], intra-aortic balloon pump [IABP], Impella [Abiomed], and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [VA-ECMO] in selected cases); they were based a short distance (5 km) away from the referral cardiothoracic centre with fast-track transport access. In our cohort, there was only a single periprocedural death, a 91-year-old woman admitted for acute pulmonary oedema. During the BAV procedure, balloon rupture occurred with subsequent pulseless electrical activity; no pericardial effusion was detected at echocardiography. Despite a transient return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after ACLS manoeuvres and IABP implantation, the patient died in the intensive care unit. The probable diagnosis was annular rupture, but this was unconfirmed since an autopsy was not performed. However, despite the nearby cardiothoracic centre (5 km away), the chance of survival in this specific case would have been low even if the event had happened in a heart valve centre. The incidence of stroke was very low (0.5%), suggesting that major embolisation of debris from the aortic valve is a rare phenomenon. The use of left ventricular pacing through a stiff guidewire (sparing a venous puncture for a temporary pacemaker), radial access and the routine use of US-guided femoral puncture from 2019 onwards has led to a proportional reduction of vascular complications.

The 1-year incidence of death or rehospitalisation was lower in the TAVR group, but numbers were still high. These data may be explained by the fact that only 56% of B-TAVR patients proceeded to intervention (Figure 5). This result is not surprising: in a recent multicentre BAV registry, only 29% patients referred for TAVR underwent percutaneous replacement3.

Patients who are candidates for aortic valve replacement after successful BAV are discussed by the Heart Team and listed for referral to a heart valve centre. Priority is given to those with a worsening of clinical condition or readmission for heart failure. The waiting time for SAVR was on average 92±62 days (median 74 days [interquartile range {IQR} 53-142]). Even for patients proceeding to TAVR, it is already known that time on the waiting list is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In our cohort, the average delay between BAV and TAVR was 156±120 days (median: 136 days [IQR 88-193]).

The risk of death whilst waiting for intervention in routine clinical practice ranges from 2.7% to 14.0%12. In an important retrospective study, the cumulative probability of waiting list mortality and heart failure hospitalisation at 80 days were 2% and 12%, respectively, with a relatively constant increase in events according to increased waiting time13. In addition, patients classified as high risk for valve surgery have a higher waiting list mortality prior to either surgical or transcatheter aortic valve intervention than those classified as low risk. In our study, 27% of patients (n=26) in the B-TAVR group who were due to be treated died before intervention, and 27% (n=26) were admitted again for HF before intervention.

Furthermore, in the case of patients with an urgent indication for BAV due to their critical condition, it is interesting that if they overcame the acute phase and proceeded to definitive aortic valve treatment, these patients then survived up to 40 months free from readmission for heart failure.

In the palliation group, 8 patients’ (14%) indication changed to TAVR, in line with a previous report3. In the B-SAVR group, only 3 patients (38%) proceeded to aortic valve replacement; 2 patients’ (25%) indication changed to TAVR after discussion in the Heart Team. Even these data are not surprising3.

Nowadays, exponential growth in TAVR demand could overwhelm the capacity of interventional hub centres, resulting in inadequate access to care and prolonged waiting list times compared to currently available resources. A clinical evaluation 1 month after discharge could be useful to assign a targeted priority queue after BAV. In the future, the best solution would reduce the time to intervention. This point could be addressed by switching high-risk patients, already excluded from surgical intervention, to TAVR in hospitals without an onsite cardiac surgery centre. In this new scenario, other therapeutic strategies, such as direct TAVR for selected patients in centres with onsite cardiac surgery, could further reduce the time to intervention and costs.

Figure 5. Actual intervention based on the initial indication group. B-SAVR: bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement; B-TAVR: bridge to transcatheter aortic valve replacement; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Limitations

Data were collected retrospectively. It has therefore not been possible to identify if 16 patients might have undergone subsequent TAVR or SAVR in a different city or country.

Conclusions

The emerging indication for TAVR in high-risk patients has led to increasing BAV numbers. BAV is a safe and effective procedure that can be performed by trained operators in high-volume centres without onsite cardiac surgery. A minimalistic approach could reduce periprocedural complications. Despite its safety, long-term clinical outcomes remain disappointing, and a definitive treatment solution must be found without delay.

Impact on daily practice

A minimalistic aortic valvuloplasty strategy, reducing periprocedural complications, may facilitate an increase in balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) procedures for symptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis even in centres without cardiac surgery.

This strategy can promptly relieve patient symptoms until definitive treatment is possible.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.