The incidence of left main (LM) disease is reported by angiography to be ~10%1. At the root of the left coronary artery, the LM segment is divided into segments: ostial (proximal 3-5 mm), body (mid-segment, 5 mm in length), and distal (distal 5 mm). When the length of the LM is <10 mm, from the standpoint of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), most interventional cardiologists prefer to cover the whole LM segment using a drug-eluting stent (DES) unless there is a clear proximal landing zone. There are also isolated distal LM lesions, where >80% of the disease2 is seen to extend to the left anterior descending artery (LAD). Of the total number of LM lesions, ~85% involve both the LAD and left circumflex (LCX), forming distal LM bifurcation lesions3.

Criteria for LM treatment2,4 are: 1) LM diameter stenosis ≥70% measured by angiography, 2) minimal luminal area (MLA) ≤6.0 mm2 measured by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT), or 3) fractional flow reserve (FFR) ≤0.80. While the impact of LM disease location on clinical outcome after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) can largely be ignored, the question of how to stent distal LM lesions is a key issue. Of a total of 2,775 patients with isolated ostial/midshaft lesions in unprotected LM disease enrolled in the DELTA multinational registry5, at a median follow-up period of 1,293 days, there were no significant differences in the propensity score-adjusted analyses for the composite endpoint of all-cause death, myocardial infarction (MI), and cerebrovascular accident between the PCI and CABG groups, with the exception of a higher rate of target vessel revascularisation (TVR) in the PCI arm. In a recent meta-analysis6 including 29 studies extracted with 21,832 patients (10,424 in PCI vs 11,408 in CABG), for the entire cohort of LM disease, the pooled analysis demonstrated remarkable differences in ≥1 year follow-up of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), TVR, and MI, favouring CABG over PCI. Obviously, it is presumed that LM distal lesions are mainly correlated with increased clinical events after PCI. This finding is in line with two more recent large clinical trials7,8 with >3-year follow-up. In the EXCEL trial7, in which 1,905 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease (ULMCAD) and low or intermediate SYNTAX scores were randomised to PCI with second-generation everolimus-eluting stents versus CABG, ~80% of patients had disease of the distal LM bifurcation, most commonly treated with a provisional stenting (PS) approach. Although PCI provided comparable three-year composite rates of death, myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke compared to CABG, repeat revascularisation rates after 30 days were higher with PCI. In the NOBLE trial8, ~80% of patients also had distal LM involvement, again most often treated with a PS strategy. In NOBLE, PCI with an earlier-generation DES resulted in a higher composite rate of death, MI, stroke or TVR at five years than CABG.

The PS approach to true bifurcation lesions consists of placing a DES in the main branch and performing balloon angioplasty of the side branch (SB), with stenting of the SB (usually with a T technique) reserved for a suboptimal balloon result. Therefore, whether alternative approaches to distal LM bifurcation might afford superior results is unknown. In this issue of AsiaIntervention, Dejan Milasinovic and Goran Stankovic9 have systematically analysed the similarities and differences between PS and upfront two-stent approaches for LM bifurcation.

In this paper there are no further “disclosures” concerning the comparison of PS versus two-stent treatments. However, the following issues remain problematic.

Is the complexity of LM bifurcations influencing clinical outcome after PCI?

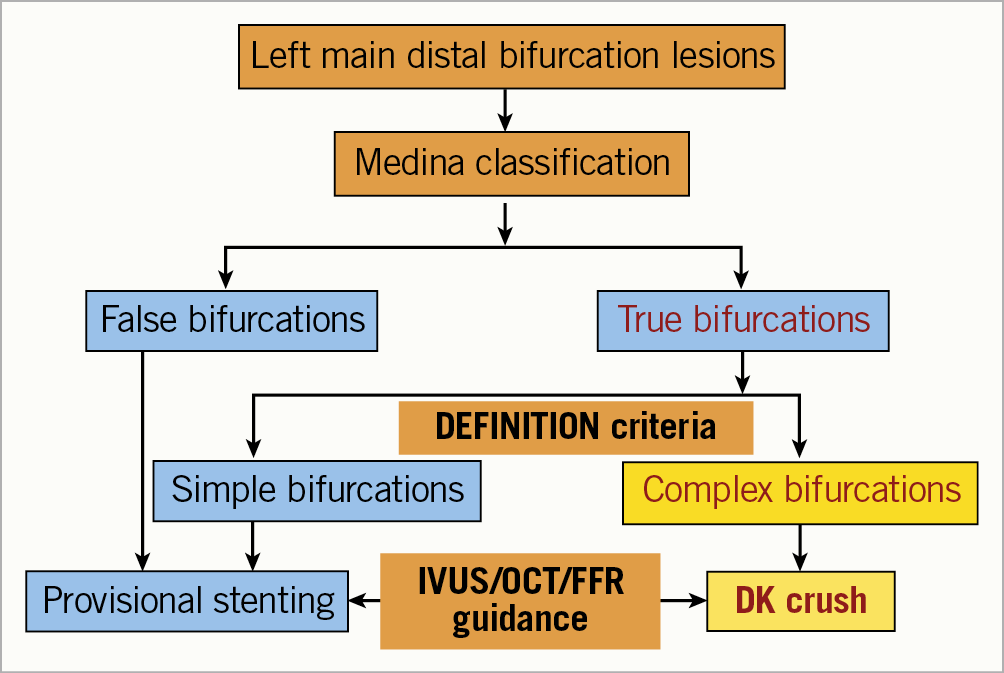

The 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularisation10 recommended the use of a systematic two-stent approach for true coronary bifurcation lesions if there is a large SB (≥2.75 mm in diameter) with a long ostial SB lesion (>5 mm), anticipated difficulty in accessing an important SB after MV stenting, or true distal LM bifurcations. However, there is a lack of widespread agreement concerning how to define complex bifurcation lesions. In 2014, the DEFINITION criteria of complex bifurcation lesions11 were developed from a large bifurcation cohort (n=1,550 patients) and subsequently validated in a 3,660-patient study. Significant reductions in mortality and in-hospital adverse events were observed in patients with complex bifurcation lesions defined according to these criteria treated with routine two-stent techniques. The subsequent DEFINITION II trial12 showed that a planned two-stent strategy significantly reduced the incidence of one-year target lesion failure (TLF) compared with provisional stenting, driven by fewer target vessel MI (TVMI) and clinically driven target lesion revascularisation (TLR). In that study, ~80% of two-stent techniques were double kissing (DK) crush, leading to the conclusion that DK crush is the winner. In fact, DKCRUSH V13, the second randomised trial comparing DK crush with PS for LM distal bifurcation lesions, reported a significant reduction of 1- to 3-year TLF in patients with complex bifurcations stratified by the DEFINITION criteria, supported by a recently published retrospective study14. Altogether, the DEFINITION criteria consisting of angiographic parameters provide the reliability of separating simple from complex bifurcation lesions and a prediction value for the occurrence of clinical events after LM bifurcation PCI.

What is the intrinsic difference between culotte and DK double crush?

Culotte stenting was and continues to be the main technique in a systematic two-stent approach for true coronary bifurcation lesions. In the DKCRUSH III study15, patients in the culotte group had a significantly higher rate of one-year major adverse cardiac events (MACE, including cardiac death, MI, and TVR), mainly driven by increased TVR, compared with the DK crush. Interestingly, the one-year MACE rate after culotte stenting for LM bifurcation lesions was similar in the DKCRUSH III (16.3%) and EBC MAIN (17.7%, all-death in this trial)15,16 trials. Furthermore, at three-year follow-up in the DKCRUSH III study17, the difference in MACE between the culotte and DK crush groups had widened, accompanied by a significantly higher rate of stent thrombosis in the culotte arm. As a result, the culotte stenting approach should be moved from the list of upfront two-stent techniques for treatment of LM bifurcation lesions.

Why is there a higher rate of periprocedural MI (PMI) after a PS approach?

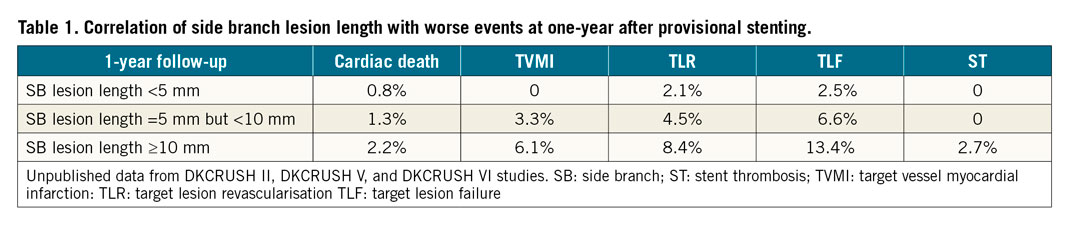

Post-stenting MI consists of PMI and spontaneous MI. The rate of spontaneous MI is comparable between PS and a two-stent approach12,13,14,15,16,17; however, the rate of PMI was significantly higher in the PS arm of the DKCRUSH V13 and DEFINITION II12 trials. In a total of 405 patients with 405 bifurcation lesions who underwent preprocedural OCT imaging of both the main vessel (MV) and the SB18, vulnerable plaques were predominantly localised in the MV and were more frequently in the long SB (≥10 mm) lesion group (42.7%) than in the short SB lesion group (24.2%, p<0.001). At one-year follow-up after provisional stenting, there were 31 (7.7%) TVMIs, with 21 (11.8%) in the long SB lesion group and 10 (4.4%) in the short SB lesion group (p=0.009). Multivariate regression analysis showed that long SB lesion length, vulnerable plaques in the polygon of confluence, and true coronary bifurcation lesions were the three independent factors of TVMI. Obviously, SB lesion length plays an important role in stenting selection and predicting worse events (Table 1), consistent with a recent meta-analysis19.

What is the correlation between PMI and mortality after bifurcation stenting?

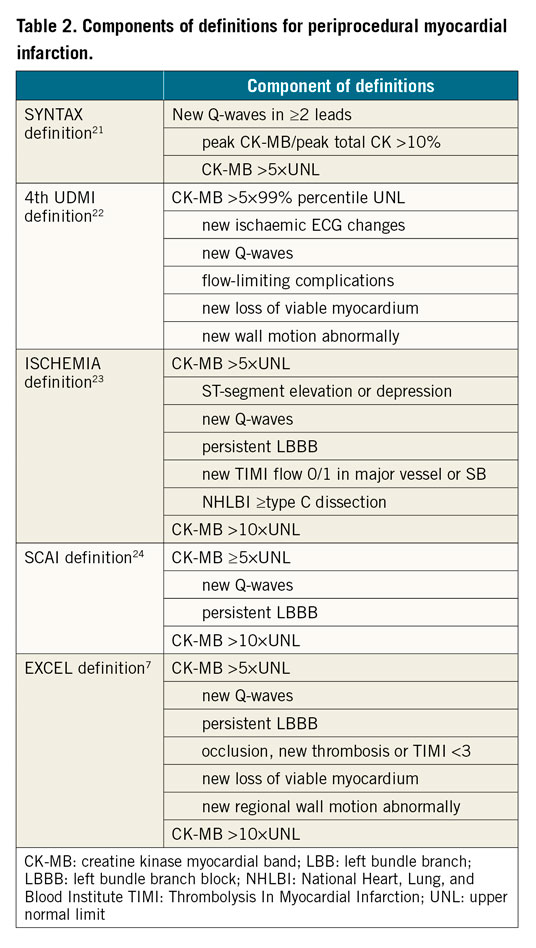

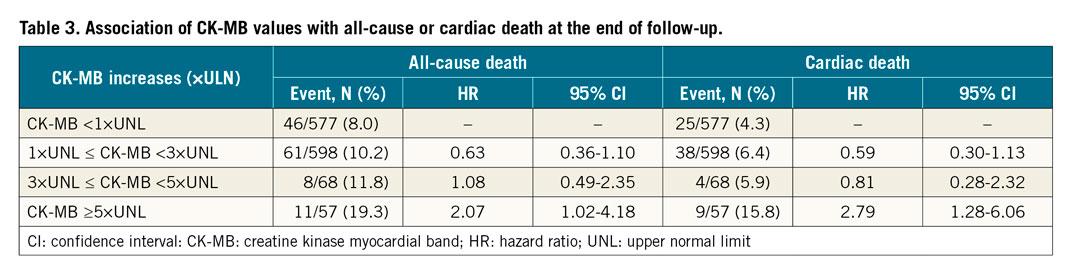

PMI refers to myonecrosis following PCI using DES. Its rate varies from 1.1% to 55.9% depending on the types and cut-off values of biomarkers and additional electrocardiogram (ECG) criteria or clinical symptoms. The pathophysiology of PMI is multifactorial and includes distal embolisation of thrombus or plaques, dissection, spasm, and occlusion of small SBs. In 1,971 patients with true coronary bifurcations who underwent DES implantation in the DEFINITION trial11, we reported that one-year mortality was significantly higher in the PMI group (defined as creatinine kinase [CK]-myocardial band [CK-MB] >3 times above the upper normal limit [UNL], 6.4%) than in the non-PMI group (1.7%). Among 1,300 patients with both CK and CK-MB measurements pre- and post-stenting were evaluated from four DKCRUSH studies20, Sheiban and co-workers reported that 56 (4.3%) patients had PMI. According to SYNTAX21, the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (4th UDMI)22 or ISCHEMIA23, SCAI24, and EXCEL7 trial definitions (Table 2), PMI occurred in 21 (1.6%), 56 (4.3%), 29 (2.2%), and 32 (2.5%) patients, respectively. All definitions were significantly correlated with unadjusted mortality at the end of follow-up but not at 30 days or one year after stenting. PMI using SYNTAX, SCAI, and EXCEL definitions rather than the 4th UDMI definition was strongly associated with adjusted all-cause death. By adjusted analysis, PMI according to the 4th UDMI, SCAI, and EXCEL definitions (but not the SYNTAX definition) was positively correlated with cardiac death at a median of 5.58 years of follow-up. CK-MB ≥5×UNL strongly enhanced the correlation of CK-MB values with mortality (Table 3). Accordingly, intravascular imaging guidance of bifurcation stenting is critical for improving clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Stenting LM bifurcation lesions is technically demanding. Careful assessments according to angiography, intravascular images, and/or fractional flow reserve (FFR) are key points of device and approach selection (Figure 1). The quality of stenting procedures determines the short- and long-term clinical outcomes. DK crush is associated with less frequent worse clinical events, particularly for complex bifurcation lesions defined according to the DEFINITION criteria.

Figure 1. Algorithm of stenting left main distal bifurcation lesions.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.